IT was April 1995, and I was preparing to travel to Afghanistan for my first volunteer post with a UK charity. I had travelled to London to meet the Afghanistan director for the non-governmental organisation (NGO) I was going to be working for and now sat in their tiny office facing him. My father had travelled to Afghanistan in the 1970s and loved it. His stories had mesmerised me. After years of dreaming about going to Afghanistan, I would finally be on my way.

I was nervous and had no idea what to expect. Would I find the war-torn nation I had read about in the newspapers or the beautiful country photographed by Roland and Sabrina Michaud – photographers who roamed Afghanistan in the 1970s and captured a wealth of faces and landscapes in their incredible photobooks? I asked the director about the threat of the Taliban. He said: “Sippi, by the time the Taliban take Afghanistan, I’ll be dead and you’ll be an old lady.”

How wrong he was.

Back then, the Taliban were generally considered to be just another faction of the Mujahideen, the Muslim fighters who rose up to push the invading Soviet army out of Afghanistan. Many thought they were so extreme that their early successes would be short-lived and of little consequence. I put them out of my head.

I was 25 at the time. But by the time I was 27, towards the end of 1996 – and still living in Afghanistan – the Taliban had taken most of the country. After the events of September 11, 2001, however, Afghanistan was invaded by US, UK and NATO forces, which displaced the Taliban and installed a new government. But the Taliban never went away and the new regime didn’t last. And in August this year, what I had long expected finally came to pass – once again, the Taliban were in power. Towns, checkpoints and any form of resistance had just toppled like so many dominoes before them.

First impressions

I had been studying Afghanistan for some time before I landed on a dusty airfield in 1995 and began work in Faizabad, Badakhshan, a remote, conservative backwater in the remote and mountainous northeast of the country. It was inhabited mostly by Tajiks with a mix of other ethnic groups, including Pashtuns and Uzbeks. The country was poor before the war against the Soviet army. But after the war, what little infrastructure had been built was destroyed and there was no budget to restore it or even to employ civil servants.

Throughout my years in Afghanistan, I have always been taken aback by the number of communities where there has never been a school, clinic or government building. In Badakhshan, I watched children with empty oil cans on their backs collecting every animal dropping on the road to burn as fuel at home. In Kabul, I watched adults and children pick through the rubbish heaps looking for food to eat and material to recycle.

The small town of Faizabad, cut in half by the furious and noisy Kokcha river, was full of men with big beards and semi-automatic rifles. Women, meanwhile, all walked around in burqas in public places. I quickly made friends among them, being the only foreigner there at the time. When hailed by one of them in the local bazaar, I couldn’t always recognise the voice, so I would clamber in under their burqas to see who they were and we would have a chat in our private blue tent.

But the differences between the smaller villages and the capital, Kabul, could be stark. Once, during a visit to Kabul before the Taliban took power, I was shocked to see men in suits in offices and women working in the ministries. I wasn’t even allowed female visitors in my office in Faizabad, and had never seen a man in a suit there. So in 1996, when the Taliban arrived in Kabul, where I was living, they brought to the capital a way of life I had already experienced in Badakhshan.

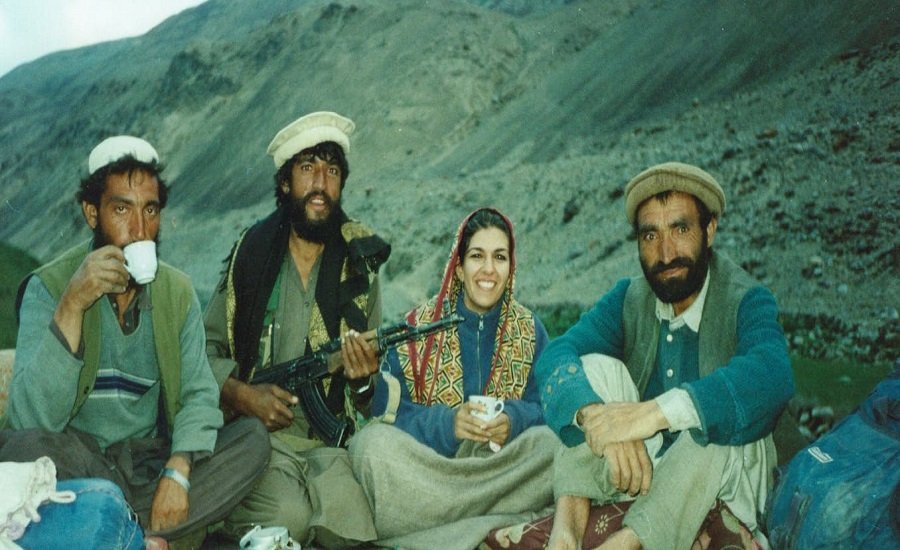

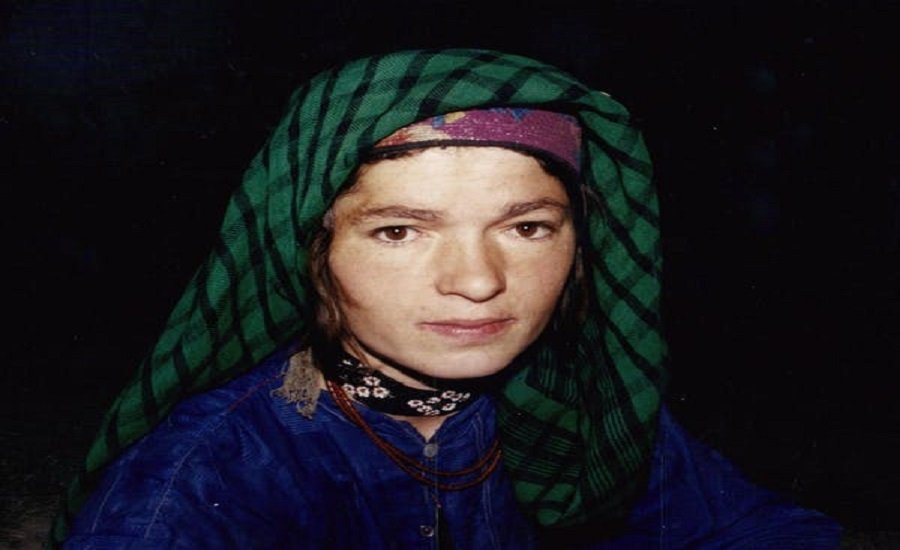

After my initial volunteer stint, I went on to work for a range of NGOs in Taliban-controlled areas. From early 1997, alone with one Afghan driver, I travelled all over the country, doing work on rural development and often focused on helping women.

This was all very unusual. When I started working in Afghanistan, the atmosphere was often tense and fearful because of the actions of some local commanders – murder, rape and looting – were rife. I’d never travel alone for fear of rape and I’d be stopped at checkpoints where militants would ask for money or try to steal things out of my luggage. But things started slowly to change under the Taliban. The Taliban were fine with me accompanying female staff to work in villages and they supported limited activities for women.

Of course, women had to wear burqas and the activities had to be within the bounds of Islam, as the Taliban interpreted it. But before the Taliban – when much of Afghanistan was run by an array of Mujahideen warlords – it was dangerous taking any female staff on journeys because of the likelihood of rape, and at times we faced a lot of restrictions. People who ran projects in the 1980s I spoke with, for example, had great difficulties accessing women in communities and some struggled to get parents to accept that girls should be educated, even in home schools. But this, too, gradually began to change. Some NGOs were requested by communities to build schools for girls. I worked for one of them and we continued building girls’ schools after the Taliban took power.

At the height of Taliban power in the late 1990s, I was often in Kabul working on women’s issues and was once again able to negotiate women’s presence in projects. Throughout this period, I met Taliban ministers, governors, commanders, foot soldiers and the dreaded “vice and virtue” police.

I faced all sorts of attitudes and it was not an easy time for my Afghan colleagues. But we manoeuvred through it somehow. After the fall of the Taliban in 2001 I continued my work with NGOs, the UN, donors, NATO, the World Bank and the Afghan government. I continued my travels and my interest in the Taliban grew, especially thinking back to what I had witnessed from 1996 to 2001.

I began to think more deeply about how the Taliban was portrayed and how the situation wasn’t as black and white as many in the international community tried to paint it. I realised that my experiences were very different to the “official narrative” about the Taliban and I began to wonder why. I pondered whether framing the Taliban differently would have led to different outcomes for Afghanistan.

A movement for turbulent times

Questions started to form in my mind about the Taliban’s identity and how it differed from other Mujahideen factions. For example, Ahmad Shah Massoud, the photogenic leader of Jamiat-I Islami, one of the most powerful of the Afghan Mujahideen groups, was a typical Mujahideen warlord – a charismatic orator who was larger than life.

In contrast, Mullah Omar, the founder and original leader of the Taliban, who died in 2013, was a recluse. He had lost an eye during the war against the Soviets. In this sense, he reminded me of other, mystical figures from the region’s past, such as Al-Muqanna (“the veiled one”). Born in Afghanistan in the eighth century and deformed when a chemical explosion went wrong, he led to a popular rebellion against the ruling Abbasid dynasty.

The followers of Al-Muqanna, like the Taliban in those early years, wore white. Was this a coincidence? History repeating itself? For the masses, all this added to the strangeness and, for some, allure of the Taliban.

I started researching the Taliban’s use of events – usually violent ones – to enact a performance demonstrating their power. I realised that this was not simply violence for violence’s sake. It was crafted to have an impact on a specific audience, conveying a message that was usually about projecting their power and legitimacy.

I realised that this kind of violent “performance” was their “language”. If we look at their actions as simplistic, savage, backward or misogynistic, as many do, we miss the opportunity to learn how to face them on this particular battlefield. And it is a battlefield on which they never really faced a sustainable challenge, as their return to power this year suggested.

It is worth remembering that the Taliban emerged during a hugely violent period in Afghan history. All of the major factions were involved in killing, raping and looting on an alarming scale.

The Taliban’s origin story tells how Mullah Omar was approached for help after local warlords raped some young girls at a checkpoint. The Taliban, then, emerged from vigilantism against local commanders whose depravity and violence against people had become intolerable in the southern province of Kandahar. For westerners who were shielded from the daily violence of life under the Mujahideen, the Taliban were only different in revealing their violence publicly. Other factions kidnapped, raped, tortured and executed – but often away from the western gaze.

I remember troops arriving in Kabul from the Junbish faction, a Turkic political group, in 1996, shortly before Kabul fell. They had come to support Jamiat forces – from the oldest Muslim political party in Afghanistan – as they stood to lose Kabul. There was tangible fear throughout the population, especially among women. People remembered the disappearances, the rapes and the mutilated bodies from previous periods when Junbish had ravaged Kabul’s suburbs. Violence was always a grim background soundtrack to people’s lives at the time.

When I look back, it is clear that the Taliban were very visual and performative in their presence in the public space – and this is what gave them power. They did not, for example, simply tell people to keep their hair short; they would grab people and give them haircuts by force. They also had a stick specifically for checking whether men were shaving their genital area as instructed. Their actions spoke of domination and authority. They had a deep impact on Afghan society through fear. Every story told by Afghans since then links back to something which happened to them under the Taliban. They got inside people’s heads.

The Taliban movement developed out of a long-term process of Afghan state formation, transformation and collapse which left the Afghan people in poverty and a bloody civil war raging. What has become clear to me, with the benefit of hindsight, is that through violent performances around power, rule and justice, the Taliban created a political space which belonged only to them. In many ways, the behaviour of ISIS in Syria and Iraq, including the destruction of antiquities, mimicked the Taliban in this early period.

In my ongoing research, I am charting those early years. The sociologist Jeffrey Alexander, who has analysed power and performance during the Arab Spring and the turmoil during and after September 11, states that the ability to mobilise cultural elements to move audiences is the basis of political power.

The Taliban have mastered social performances of power using a language which is visual and visceral. They bring together shared narratives and beliefs from Afghan history and culture in the Muslim period to create new stories about who they are and the state they intend to create.

Three events in particular reveal the Taliban’s mastery of this kind of performance. They also mark major phases in how the Taliban identity developed.

1. The Prophet’s cloak

One of Mullah Omar’s first such actions, in 1996, was extraordinary. He removed a holy relic from a shrine in the city of Kandahar – itself a historic former capital where wars had been waged by mighty empires, as depicted in the Bollywood blockbuster, Panipat.

This relic was a cloak which Muslims believe belonged to Mohammed, the holy prophet of Islam, who wore it on the famous journey from Mecca to Jerusalem, completed in one night, around 621AD. The object was brought to Kandahar in the 18th century from Bukhara, in modern day Uzbekistan, by Ahmad Shah Durrani, founder of the Durrani empire and the modern state of Afghanistan. It is a relic to which miracles are attributed.

Mullah Omar was famously camera-shy. So shaky and grainy, secret camera footage showing him – his arms inserted into the sleeves – with the garment, which he was holding aloft to a large Kandahar crowd, is uncharacteristic and dramatic.

There was almost always a build-up to these events. In this case, religious leaders had come from across Afghanistan and beyond. The Taliban had to decide whether their fight would end in Kandahar or whether they would move on to claim Kabul. But Mullah Omar was declared Amir ul-Mo’menin (Commander of the Faithful), giving him the religious and political authority to lead the Taliban to Kabul and to establish the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan.

By touching this venerated object before the gathered crowd, the leader of the Taliban was claiming Muslim and Afghan legitimacy by association with the Prophet Mohammad and Ahmad Shah Durrani. This action stated clearly that he had not arrived there solely by the power of the gun and that he was not an ordinary leader of a Mujahideen faction. He was putting himself in the line of descent from the Prophet of Islam and the Durrani kings of Afghanistan. He was claiming moral and religious authority to put his arms in the sleeves of this venerated object.

Although the Mujahideen had been branded holy warriors in their war against the Soviet army, and its leaders had claimed moral authority, none had stated it in such dramatic and symbolic terms before a crowd of thousands.

This relic had rarely been seen by the public – it had last been removed from the shrine decades before, during a cholera outbreak – so being confronted with it in this way was the closest thing to a miracle for those gathered. The crowd started chanting “Allah-o akbar” (God is great) and “Amir al-Mo’menin” (Commander of the Faithful).

2. The dead president

In a photograph which exploded like a bomb the day after the Taliban first took Kabul in late September 1996, two young Taliban foot soldiers hug each other with joyful faces under the grotesquely deformed and bloodied figures of former President Najibullah and his brother, hanging from a traffic light pole in Aryana Square.

After establishing their religious credentials in Kandahar, the Taliban sought to convey anti-corruption and justice messages, especially in Kabul, which they considered a den of iniquity. Before arriving in Kabul, the Taliban had already started their acts of performative violence, indicating that they intended to dictate and dominate people’s private lives.

TVs, videos and music cassettes were banned – and not simply by edict: smashed TVs dangled at Taliban checkpoints like blinded eyes, cassette ribbons flew in the wind like the entrails of eviscerated creatures executed and displayed like trophies.

Indeed, the execution of the former president was the Taliban’s brutal and very public message to the people of Kabul on the first morning of their rule in the city. No exceptions would be made and everyone who deserved punishment would receive it.

But why Aryana Square and why President Najibullah?

Aryana Square is at a crossroads at the heart of Kabul’s historic centre. It is very close to the Arg, a fortress-palace built by Abdur Rahman, the “Iron Amir”, who consolidated Afghanistan and built the foundations of the modern Afghan state. The Arg was constructed after the Bala Hissar fortress was destroyed by British Indian troops during the second Anglo-Afghan War in 1880. Occupation of the Arg has played a symbolic role in modern Afghan history, with the centre of Afghan state power remaining within its walls, except for the period when Mullah Omar ruled from Kandahar.

Regime change in Afghanistan is almost always bloody. Mujahideen commanders before the Taliban had done a great deal of killing, but these deaths were in secret, in assassinations or in firefights. There had never been a public execution of a prominent public figure with the body displayed like a common criminal. But in the case of the Taliban, there was no hiding the killing and torture of the former president, beloved by many for his charisma and loathed in equal measure by the thousands who had disappeared into prisons never to emerge.

This was not a senseless, spur of the moment killing. Najibullah was ethnically Pashtun – like the Taliban – and was under the protection of the UN. When the Mujahideen leaders and commanders abandoned Kabul prior to the Taliban takeover, they had offered to take him. Yet he stayed, confident he could talk the Taliban around because they were fellow Pushtuns. The killing can be interpreted in many ways: that the Taliban were not going to make exceptions for a fellow Pushtun; that the authority of the UN meant nothing when the Taliban wanted to mete out justice for those killed by the Communists; or that the Soviet invasion ended here with the killing of their last protégé. Some have accused Pakistan intelligence forces, ISI, of using the Taliban to dispose of one of their foes.

The bodies, castrated as a further expression of their powerlessness in the masculinised Taliban public sphere, were left to hang there for three days. Announcements had been made on the radio and thousands of people gathered to view the scene with shock and dismay. The spectacle of Najibullah’s execution was the first of many. It was meant to cow the population of Kabul into submission and to set the Taliban up as Islamic arbiters of justice and morality.

These killings made a deep impression which lasted long after the Taliban were toppled. After this, in Kabul as elsewhere, the burqa was forced on women and beards, short hair and head covers on men. Through the personnel of the Office for the Prevention of Vice and Promotion of Virtue, the Taliban policed how people behaved and dressed. And women’s presence in public had to be moderated by a mahram (a male relative).

3. Vandalised antiquities

One of the most dramatic actions of the Taliban was the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddha statues, located in the central highlands of Afghanistan in 2001. This event made the Taliban notorious globally.

One of the most celebrated tourist sites in Afghanistan before the war, the Buddhas were described as priceless artefacts – the largest standing Buddha carvings in the world.

The first attempt to destroy the Buddhas came when the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb tried to use heavy artillery to destroy the statues in the 17th century. He only succeeded in damaging them during the attack. Another attempt was made by the 18th century Persian king, Nader Shah Afshar, who directed cannon fire at them.

It is also claimed that Afghan King Abdur Rahman Khan destroyed the face of one of the Buddhas during a military campaign against the Shia Hazara rebellion (1888-1893). And there were rumours about the British using the Buddhas for artillery practice in the 19th century. According to the ethnologist Professor Pierre Centlivres, 19th century travellers were already noting that the Buddhas lacked faces. The Taliban, however, in keeping with their violent power performances, went for something a bit more systematic and spectacular.

In 2000, the UN Security Council imposed an arms embargo on the Taliban to pressure them into breaking their ties with Osama Bin Laden and to close terrorist training camps in Afghanistan. In response, Mullah Omar issued a decree on February 26 ordering the elimination of all non-Islamic statues and sanctuaries from Afghanistan. The Taliban began smashing Buddhist statues in Kabul Museum from February 2001 onwards.

Inevitably, there was international outcry. In his memoirs, Taliban minister Abdul Salam Zaeef notes that UNESCO sent 36 letters of objection to the proposed destruction. The Chinese, Japanese and Sri Lankan delegates were the most vociferous advocates for the preservation of the Buddhas. The Japanese offered a number of solutions, including payment. UNESCO, New York’s MET museum, Thailand, Sri Lanka and even Iran offered to buy the Buddhas, and 54 ambassadors of the Organisation of the Islamic Conference conducted a meeting and protested their destruction.

CNN reported that Egypt had preserved its ancient pre-Islamic monuments as a point of pride, and Egypt’s president, Hosni Mubarak, dispatched the mufti of the republic, the country’s most senior Islamic authority, to plead with the Taliban.

The 22 member Arab League condemned the destruction as a “savage act”. Pakistani president Pervez Musharraf sent his interior minister, Moinuddin Haider, to Kabul to argue against the destruction on the basis that it was unIslamic and unprecedented. The southeast Asian media reacted with deep shock. The Indian media blamed the US for putting its interests in oil and gas ahead of saving the Buddhas.

The substantial task of destroying the statues in the Bamiyan valley started on March 2, 2001 and took place in stages, over 20 days, using anti-aircraft guns, artillery and anti-tank mines. Eventually, men were lowered down the cliff face to place dynamite into cavities to destroy what was left.

To ensure an international audience and widespread media coverage, 20 journalists were flown to Bamiyan to witness the destruction and confirm that the two Buddhas had been destroyed. Footage of clouds of dust billowing out of the niches, where two giant Buddha statues had stood watch over the Silk Route winding through the Bamiyan valley for millennia, was transmitted all over the world, as the international community watched in horror and dismay.

The Taliban had sought – unsuccessfully – to obtain acceptance of their regime by the international community. The sacrifice of the Buddhas can be interpreted as a symbolic act announcing the end of any conciliatory gestures. This was an assertion of power by spectacle. The internet, relatively new at that time, intensified the impact of the destruction of the Buddhas.

Taliban #2

Since 1994, the Taliban’s actions have all been part of a non-verbal soliloquy, responding to the ghosts of imperialism, colonialism, neo-imperialism and neoliberalism. The group uses public spaces in Afghanistan very much like a stage.

Violence is used as a kind of power performance to convey messages and responses to history. The performances are not random. They are thought through. They can be interpreted on many levels. They speak of discourses in worlds the western audience is not privy to.

The Taliban ushered in a new phase in a long discourse on Islam and the state in this region. Despite those initial dismissive analyses which saw the Taliban as madrasa-educated yahoos from Pushtun backwaters (and still do), it became clear that they had in fact been trying to communicate their world vision through these types of performances. If this had been understood, negotiations with the Taliban may have led to very different results and the long war, which has claimed so many lives, avoided.

This time round, the Taliban is tapping into other codes and symbols. In particular, their latest performances have involved their special forces, the Badri 313 unit. These soldiers are extremely well equipped and almost a mirror image of special forces units from other parts of the world. This simple act conveys messaging about the Taliban’s victory, and them being on an equal footing with the American soldiers in the same uniforms.

We have also seen shots of Taliban soldiers wearing clothes worn by southern Pushtun tribespeople. By wearing traditional clothes, outmoded hairstyles and flimsy sandals, they send a message about their claimed background and physical resilience. It also invokes hints of nostalgia, for a time of warriors past, when the Pushtuns were a formidable foe.

After entering Kabul, Taliban fighters and leaders posed for photos in the Presidential Palace, congregating at one point under a painting depicting the crowning of Ahmad Shah Durrani. Although some have commented that this is incongruous with the identity of the Taliban, I would argue that one has to look back to their previous rule. In my view, the Taliban symbolically established a political lineage reaching back to Ahmad Shah through Mullah Omar’s appearance with the cloak of the prophet in Kandahar. But the significance of many of the Taliban’s actions were missed at the time by commentators eager just to write them off.

Most interesting to me was when Sirajuddin Haqqani – leader of the powerful and feared Haqqani faction in the Taliban and now interior minister – met with the families of suicide bombers, praised their sacrifices and gave them gifts of land and money. Suicide bombing was a key part of the Taliban’s battle against the previous government. But the previous regime rarely publicly acknowledged the deaths of their ordinary soldiers and police – they were literally cannon fodder. They certainly did not have public ceremonies to honour the sacrifices of the Afghan people. The government had even hid casualty figures for a while to avoid demoralising the nation.

Months before the Taliban arrived in Kabul in 2021, I watched as they closed girls’ schools in the north. This was also a power performance. It was a challenge, a gauntlet cast down for the Afghan government to pick up. It did not simply show that the Taliban objected to girls’ education. They were demonstrating their power by taking away one of the advances the Afghan government had consistently showcased to the international community as a major “gain”. Perhaps it was also a signal to outspoken Afghan women and their supporters that the Taliban were not interested in being conciliatory on women’s rights.

I waited for an equivalent and “in kind” response from the Afghan government, women’s rights activists or the international community. A team sent to negotiate; a military unit sent to retake the schools; the girls offered education elsewhere – at the time, the Afghan and international military were present and could have made some sort of symbolic gesture in response.

But nothing happened. Nobody, it seems, understood the Taliban’s mode of power performance. The only response was the usual verbal condemnation on social media. The Afghan government showed itself as powerless and abandoned those school girls as it would eventually abandon the rest of the population. Once again, the world watched, frustrated and uncomprehending, as the Taliban rewound Afghanistan right back to the days before they were toppled in 2001.

_______________

The author is a PhD Candidate in International Relations, University of St Andrews.

c. The Conversation