Now that Afghanistan has got a new elected leadership and government in place, finding a political end to the fighting is essential for Afghanistan’s long-term stability. Thousands of NATO troops could not help the government quell the insurgency and establish control over the entire country. The only realistic way to prevent the continuation of this violent stalemate is a negotiated end to the war.

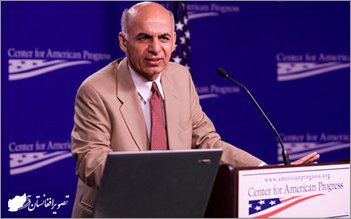

DR MALEEHA LODHI

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he advent of a new government in Kabul marks a hopeful moment for Afghanistan after months of political turmoil and uncertainty. A government of ‘national unity’ ushers in an unprecedented experiment in power sharing between opposing political groups and their disparate allies, with obvious ethnic overtones.

This nonetheless offers an opportunity to set the country on a stable course and steer it along an orderly path to meet the challenge of the transitions that lie ahead – security, economic, political, and regional.

The first and most immediate challenge for the Ashraf Ghani-Abdullah coalition is sustaining the American-brokered ‘unity’ deal that enabled the political transition to proceed after a bitterly disputed election. But what many would regard as a shot-gun marriage, forged under American pressure, also reflected the acknowledgement by both leaders of the imperative to work together – and the disastrous consequences for the country if their accord unraveled.

Both know that international aid and assistance will only flow if the two stick together. They are also acutely aware that if their coalition does not endure this would expose Afghan security forces to the risk of fracture.

Even so, questions continue to be raised about the stability and long-term survivability of the ‘unity’ coalition. As always, the devil is in the detail of working such a complex arrangement. As this is likely to be high-maintenance, how much hand holding will American officials be able to do to preserve the coalition?

For both President Ghani and chief executive Abdullah, a formidable challenge will be to manage their fragile coalitions of supporters, which includes regional strongmen and former warlords, who remain bitter rivals of each other. The risk of parallel governments will need to be mitigated by the demonstration of exemplary accommodation between the two leaders, especially on key appointments.

The second important challenge is posed by the stance and activities of the armed opposition, the Taliban, who have exploited the uncertainty of the past several months by stepping up attacks, especially in the south and east. The Taliban also seem to be changing tactics – shifting to larger scale ground attacks from reliance on IEDs.

Although one part of the political transition has taken place, a successful transition has always meant more than a transfer of power. Its other crucial aspect involves launching a peace process that the Taliban can be persuaded to join and that eventually yields a political settlement.

In his inaugural speech, President Ghani signalled that ‘reconciliation’ would be a priority on his agenda, but the question is what kind of on-ramp is offered to the Taliban into a political process they deem to be in their interest to join. That Ghani isn’t Karzai certainly opens space for a reconciliation initiative.

For now, Taliban spokesmen have rejected Ghani’s offer for talks and cast his administration as ‘made in America’. But this is far from being the last word, especially as Taliban leaders probably realise that their fighters may be tiring of endless war.

Finding a political end to the fighting is obviously essential for Afghanistan’s long-term stability. The Taliban do not – by all indications – have the capacity to overrun the country, much less take Kabul. But it is also true that tens of thousands of Nato troops could not help the government quell the insurgency and establish control over the entire country. The only realistic way to prevent the continuation of this violent stalemate is a negotiated end to the war.

This is all the more necessary because doubts linger about the security transition once Nato’s combat mission ends in the coming months. Although Afghan security forces performed well to secure two rounds of the Presidential election, there are questions marks about the Afghan National Army’s (ANA) ability to stand its ground when Nato’s military drawdown is completed.

Afghan security forces have been suffering much higher casualties. This summer alone, its casualties exceeded those suffered by Nato forces in 13 years of war. Issues of training deficits, morale and ethnic balance persist. Moreover, the country’s defense establishment has been asking for post-2014 air, intelligence and logistical support. What assistance the US will provide in this regard, especially airstrike capabilities, is unclear.

The new government quickly signed the much-delayed Bilateral Security Agreement with Washington to provide for a residual US/Nato military presence. How far this much smaller force of around 12,000 troops on a ‘train and advise’ and counter-terrorism mission is able to deal with an intensifying insurgency remains an open question. After all, a much larger force, with air capabilities, was unable to achieve the military goal of defeating the insurgency.

The new government’s ability to manage the economic transition, as aid levels begin to fall, will also have a crucial bearing on the security situation. This involves not just the immediate payment of salaries to government employees and security forces, but dealing with the recessionary economic impact of the drawdown of Western forces.

The next three months will be critical in indicating how the Ghani-Abdullah coalition is able to address these imposing challenges and whether it can build stability on the tripod of security, reconciliation and the economy.

How is Pakistan viewing the evolving situation? It sees the new Afghan government and the exit of the unpredictable Hamid Karzai as an opportunity to coordinate more closely with its neighbour and to resolve differences that emerged in the recent past.

Islamabad has already signaled it is ready to extend all possible help – political, security and economic – to the new dispensation in Kabul. It would also be ready to play a supportive role in political reconciliation between Kabul and the Taliban, if asked to do so.

Pakistan’s central post-2014 priority will be to secure its border. Its military campaign in North Waziristan, aimed at eliminating the last hub for assorted militants in Fata, has already seen the dismantlement of the infrastructure of militancy there. The operation has marked a decisive effort to secure the border, ahead of the Nato troop drawdown. Other than address a critical internal security challenge, this will help to stabilise the border as well as enhance regional security.

It also paves the way for Pakistan and Afghanistan to operationalise joint plans for border security and to eliminate safe havens on both sides. In the past, Pakistan was disappointed by the lack of response from the Karzai government to its proposals to install more robust border control mechanisms.

For example, before and after the launch of Operation Zarb-e-Azab, there was no complementary military effort on the other side of the border. Earlier this year, Pakistan also gave the Afghan government a proposal for bilateral border SOPs, to provide a framework for cooperation to replace and upgrade the tripartite SOPs, which were in place between Isaf, Afghanistan and Pakistan. This did not elicit a positive response.

Islamabad is hopeful this will change under Afghanistan’s new management as both sides see a chance to make a fresh start. And while Islamabad has security concerns over the unknowns surrounding Afghanistan’s transitions, it also believes that Afghanistan – and the neighborhood – have a fresh opportunity to establish lasting regional peace and security.

Such a positive outcome depends primarily on how successfully the new Afghan government deals with its internal challenges and political rifts. But it also hinges on the role of external actors and especially whether a regional consensus on non-interference is implemented in Afghanistan. This would involve a commitment that everyone in the neighborhood plays by the same rules, and in a potentially fluid situation, no regional power tries to take advantage of any security vacuum.

Certainly no dominant or ascendant role should be assigned to any regional state. This would be an invitation to regional rivalries and represent another variation of the many Great Games of the past, which brought so much grief to Afghanistan and the region, and to Pakistan.-c. The News International