Clarion India

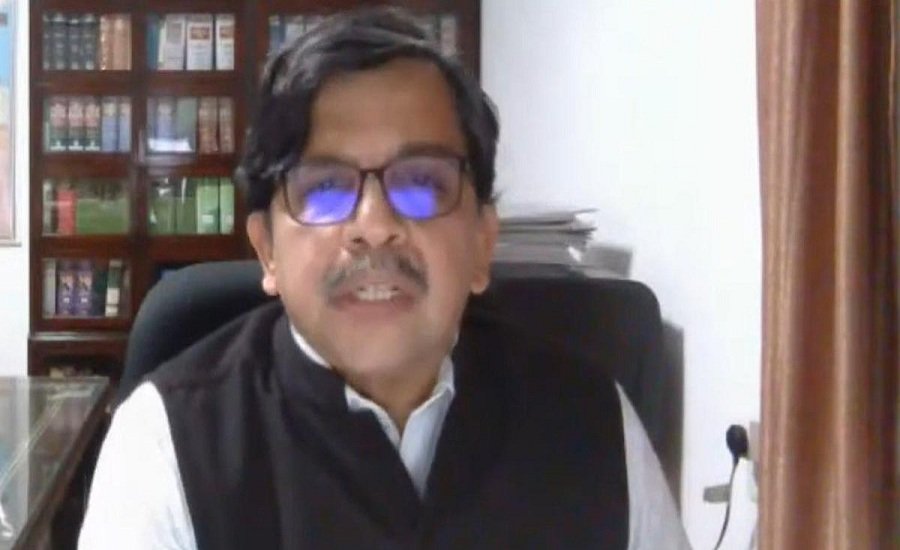

NEW DELHI – “There are many barriers to accessing justice that a marginalised person faces. The laws and processes are mystifying even for an educated literate person. The laws are themselves structured to discriminate against the poor,” said Orissa High Court Chief Justice S Muralidhar on Thursday.

He made the observations when he was delivering a lecture on the topic “Appearing In court: Challenges In Representing The Marginalized”, to mark the 131st anniversary of BR Ambedkar.

In his lecture, Justice Muralidhar pointed out that 55% of the 3.72 lakh people in India who are awaiting trial, belong to the Scheduled Caste and Other Backward Classes, Live Law reported.

Of the 1.13 lakh convicts, 21% belong to the Scheduled Caste and 37.1% to the Other Backward Class category, Muralidhar said. More than 17% of those under trial and 19.5% of the convicts are Muslims, the Odisha High Court chief justice said.

“Yet these are the persons who are likely to find it difficult to come forward to fight for their rights,” he said.

He added that many people who are under trial continue to remain in jail despite being granted bail because of their inability to arrange surety bonds, Live Law reported.

Muralidhar also expressed concern about the quality of legal aid in the country for those unable to afford legal representation.

“The lack of confidence in the legal aid lawyer is a reflection of the general approach to welfare services by the providers,” he said. “I call it the ration shop syndrome. The poor believe that if you get any service for free or it is substantially subsidised, then you cannot demand quality.”

The chief justice also cited a study that found that human rights lawyers belonging to Dalit and Adivasi were labelled as “Maoist or Naxalite lawyers”.

“Unfortunately, there is a tendency of late to view appearing for the marginalised as making a political choice,” he remarked.

He said that people from marginalised groups largely viewed the legal system as irrelevant to them as a tool of survival and empowerment.

“Their experience tells them that it [the legal system] operates to oppress them and they have to devise ways to avoid it rather than engage with it,” Muralidhar said. “We need to revive discussions around decriminalising many of the surviving activities of the poor.”