Language lives through the people who use it.. It’s an ever-evolving phenomenon, changing with the times. Like a river, it is unstoppable and endless, taking from the banks what it will, losing some of itself on the way and in so doing, nurturing the general climate of the place

OZMA SIDDIQUI

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he mix of different societies through the ages has given rise to an amalgamation of cultures helped by a blending of languages, growing and enriching each other with their unique flavors of syntax, idiom and phrase. Each language carries with it a taste of the soil from which it sprung. Urdu, for example, is full of words from Hindi, Persian, Arabic and English — the last being a legacy of the colonial past of its speakers. Language lives through the people who use it.

It is an ever-evolving phenomenon, changing with the times, taking on new meanings and linguistic features in the context it is used. Like a river, it is unstoppable and endless, taking from the banks what it will, losing some of itself on the way and in so doing, nurturing the general climate of the place. Given the universal quality of language then, it’s hard to classify it as belonging to a particular group or representative of only a certain class or culture.

However, to take up this argument on its own merit, perhaps it is only fair to admit that language can and does represent a people and its culture. But is it also fair to throw away the baby with the bathwater and dump a whole language in its entirety because some aspects of the culture it represents are unacceptable?

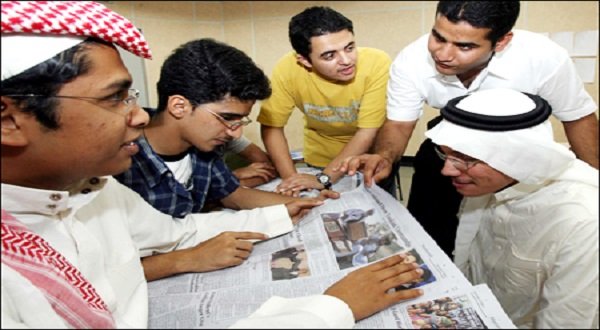

Recently, a fiery debate has arisen over whether English should be taught in Arabic schools. Is the point really that English should not be taught in Arabic schools because it threatens the survival of Islamic culture or is the real issue that English represents all that is Western and therefore foreign to us?

If the latter is the dilemma, it is indeed surprising that other facets of Western culture have not been dealt with in the same way.

Our youth cruise about in expensive cars at 180km/h on crowded highways. The car is surely a symbol of Western values and all the materialism accompanying it. Our shopping malls brazenly display mannequins in all shapes and sizes, featuring clothing from some of the top names in the fashion industry. Yet never once have we heard an outcry regarding them. And it is worth saying that wearing long skirts does not necessarily make the dress more Islamic or Saudi — and in any case, the designer labels indicate otherwise.

Even the basketball and football games on Saudi Channel 2 reflect how thoroughly the West has seeped into the culture — not to mention the media — with enhanced systems of translations which make information easily accessible. It would indeed be a folly to deny its pervasive effect. Which brings us back to the question of English in schools. In all fairness, the language should be taken simply as a tool as any form of technology such as computers or Internet access. No language ever harmed a culture. If anything, it broadens horizons, opens up new perspectives and gives new meanings to things as we know them.

Every language is precious to those who speak it as their mother tongue. In fact the more languages one has access to, the more he profits from the stimuli that literature of other cultures has to offer. A recent study of languages revealed that the languages of small hunter-gatherer communities which had no chance to mix with other language groups were on the way to extinction. A language survives when it continually receives a stimulus. All living languages share this common feature.

The study further revealed that bilinguals have sharper brains. The reason is obvious: The area of the brain which deals with speech and communication is more developed than in persons who have been limited to the use of one language. It is logical to assume then that children who are exposed to two or more languages are more likely to do well than their counterparts who have not had the same opportunity.

Today, the importance of English as a window on the world cannot be denied. Practically and logically speaking, it is the right thing to do to have it in schools alongside Arabic and if possible another language as early in a child’s educational life as possible.

It is not a good idea to use a language for the purpose of nationalism or solely for group identity. Language is supposed to break down barriers, not erect them. Arabic — in common with every other language — is rich, replete with beautiful turns of phrase, poetic nuances and delicacy employed in the artistic woof and warp as it is skillfully woven to capture the imagination and provoke thought. In its own right, Arabic language has yet to find a rival to challenge its status among the languages of the world. The same may also be said of English.