Residents of the area hold title deeds to their properties dating as far back as 1920. Now they have been served evacuation notices. The anguish, pain, and anxiety are palpable.

Mohammad Alamullah / Clarion India

IMAGINE living in a place where you’ve spent decades, where your children were born, where you heard your mother’s and grandmother’s soothing lullabies, where you played all sorts of games and experienced bouts of joy and sorrow, and where you’ve seen the ups and downs of life.

Suddenly, someone arrives and tells you that this place no longer belongs to you. They demand that you leave your home within a certain timeframe, threatening to demolish it if you refuse. Can you fathom the anguish, the pain, and the anxiety you’d feel in such a situation? Can words truly capture the depth of your sorrow? Perhaps not.

For years, the people of Ghafoor Basti, located in the Banbhoolpura area of Uttarakhand’s Haldwani, have been enduring an ordeal. This area has recently been a hotspot for tensions and potential conflict. The government has issued orders for approximately 4,365 houses in the area to be evacuated. Despite possessing documents dating back to pre-independence India, residents are being forced to abandon their homes.

Upon hearing the woes of the area residents, my friends and I set out from New Delhi at dawn to see the situation firsthand.

After an eight-hour journey, we arrived to find a prayer gathering underway, predominantly attended by women. Among them, one woman was particularly distraught, crying and praying fervently, “O God, you are Merciful, we are weak. Save these homes from destruction. Protect our children from homelessness. Preserve our humble dwellings from being reduced to rubble.” The atmosphere was heavy with sorrow, and witnessing the collective grief brought tears to our eyes.

As we walked through the streets, visited teahouses, temples, and mosques, we couldn’t help but notice the pervasive atmosphere of gloom. Despite people being occupied with their daily tasks, anxiety was evident on their faces. Even the usually carefree children, known for their playful antics, appeared solemn and subdued. It felt as though a somber presence had enveloped the entire village, draining away all joy with its invisible grasp.

The young boys and girls, typically radiant with the excitement of school and college life, now seemed weary and sleep-deprived; their faces marked by traces of tears shed throughout the night.

As we traversed several streets, we reached a prominent figure seated on a post in front of a mosque. Upon learning that we had come from New Delhi, he invited us to hear the sad story of the area residents. Soon, others gathered around, and each person began recounting his experience. Curious, we inquired about the title deeds for the land in question.

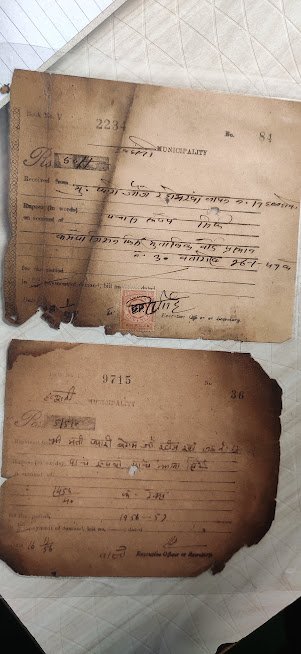

In response, many individuals, young and old alike, hurried off and returned with various documents. Some clutched files, while others held plastic pouches containing papers. They eagerly presented these documents, each one narrating a tale of ancestral ownership. “Look at this,” one exclaimed, pointing to papers dating back to 1920 and even earlier. “Our great-grandfather purchased this land before independence,” he proudly declared. Others shared stories of acquiring land through government auctions, highlighting the historical significance of their claims, especially during the tumultuous partition period when thousands of families were displaced.

We spotted an elderly person sitting at a corner. When we approached him and asked him about the lifestyle of the area residents. When he spoke it became evident that the whole locality was crying of neglect and government apathy. Heaps of garbage littered the streets, emitting a foul stench; while open drains and sewage added to the dismal situation. In the midst of all this, there were numerous open hotels, kebab stalls, and biryani shops.

A local figure, affectionately called Bide Mian (Old man), explained that the majority of the residents were daily wage earners, with a few holding government positions. While the settlement was predominantly Muslim, there was a noticeable lack of emphasis on education.

Mohammad Naeem, who operated a medical store, expressed with a heavy heart: “Ninety-five percent of the population here are Muslims; yet educational opportunities are scarce, and awareness about our rights is lacking.” He further said the government’s neglect of the area stems from the belief that the residents wouldn’t raise their voices in protest, thereby making them easy targets of oppression.

Salahuddin Ansari, residing in the area for over five decades, shared his perspective when we asked him for details. He let out a weary sigh, adjusted his clothes, and took a seat before us. With a solemn demeanor, he began his account.

“We possess all the necessary documents, and we’ve dutifully paid taxes since as far back as 1940,” he explained, unfolding a bundle of weathered papers passed down through generations. “Now, however, regardless of whether one holds these documents or not, we’re all ensnared in the same predicament. The government’s actions affect us all equally.”

He paused, and then posed a thought-provoking question: “Consider this – if the land truly belongs to the railway, as claimed by railway authorities, then where was the government all these years? How could they allow extensive development here? Why did they continue to collect taxes from us? How did they manage essential services like electricity and water? Why did they establish schools and colleges in this area?”

With a sense of frustration, he pointed out the deafening silence from the state government regarding these pressing questions.

We sought the perspective of another esteemed elder, who happened to be a lawyer deeply involved in the legal battle. He disclosed that he had filed a case in the Supreme Court on the issue. When we inquired about the broader impact beyond the houses, he enumerated a list of affected institutions: two inter-colleges, ten mosques, two temples, five madrassas, two banks, and four government schools, alongside ten to twelve private schools. He expressed profound concern, noting that while governments worldwide typically prioritize the welfare and development of their citizens; the Indian government appears to be demolishing its own institutions, settlements, and homes. Despite the challenges, he affirmed his unwavering commitment to fight for justice, even at the risk of sacrificing his life.

In our quest for understanding, we consulted another senior lawyer, M. Yusuf. He shed light on the complex legal dynamics, revealing that 70% of the city’s land is designated as nazuli – government-owned land accessible to the public, subject to government takeover if necessary. Sometimes, the government offers registry under specific schemes. He recounted the legal history: the railways initially went to court claiming six acres in 2006, then claimed 29 acres in 2016, and is now asserting ownership of over 78 acres. Despite securing stays from the court twice; the recent court decision has been unfavorable, displaying a disheartening lack of receptiveness. Yusuf expressed dismay at the court’s attitude, highlighting that amidst 900 pending land cases, clarity on the railway’s land boundaries remains elusive.

All those we interacted with argued that the entire issue was being portrayed as communal, alleging that the red flags marking areas for evacuation predominantly fall within Muslim-inhabited regions.

He says it’s a matter of communalism because the red mark has been put up in areas where Muslims live. Before Haldwani, the big station is Lal Kuan. If cleanliness starts from there, then all the areas will come under the influence of Hindus. Similarly, there is Kath Godam 6 km above Haldwani, where there are Hindus living, but the action is being taken within a two-kilometer radius of Muslim areas.

There are three girls’ colleges, one college, two tube wells, 10 mosques, and two temples in these areas. Many private schools and colleges are also present separately. Then, the railway is not showing any project for which it wants to reclaim its lands. Announcements are being continuously made to evacuate the area within a week by installing microphones at the railway gate.

In our quest for clarity, we engaged with government officials. Akash Pandey, an officer with Nagar Nigam. He refrained from offering any opinion, citing the recent high court decision. He emphasized their subordinate role to the court’s directives which leaves little room for further comments.

As evening descended, we made our way back to New Delhi, grappling with a multitude of unanswered questions. Are Muslims truly becoming strangers in their own country…?

Will they continue to face similar targeting despite their significant sacrifices…?

These questions lingered in our minds, haunting us even as we journeyed home.

All these questions beg a satisfactory response from all stakeholders.