J Devika

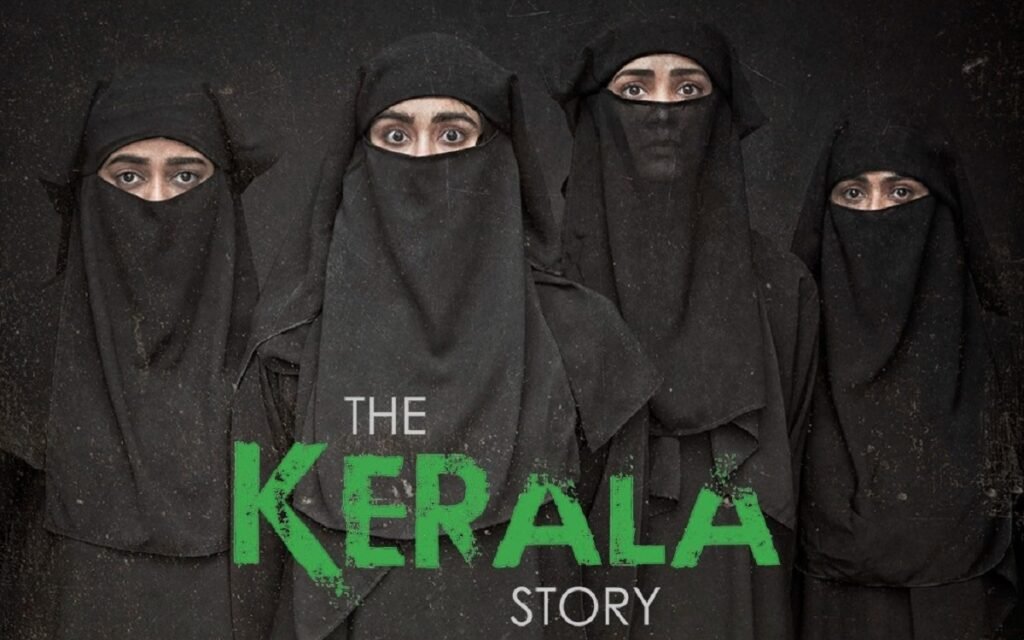

THE movie called The Kerala Story is hate-speech against a whole people, but our courts are great upholders of free speech. Of course, unless people with the surname ‘Modi’ are said to have been defamed. As an observer of how the ‘love jihad’ agenda has unfolded in Kerala since more than over a decade now, I think we need an explanation of why the very idea, discredited by the state machinery itself and thrown out in effect by the Supreme Court in the Hadiya Case, has been used over and over again, like a hammer, to beat Kerala (hopefully into a shape acceptable to Hindutva).

I think it is important to turn towards the twentieth-century history of integrating women into Hindutva politics here. It is now well-known through the explorations of feminist scholars studying Hindutva today that the Brahmanical vision of gender inequality, of women valuable essentially as mothers, that was central to the thought of its major thinkers.

The women of the RSS had no role at all in the massive effort that other women, otherwise divided by their politics — Gandhian women, women of the dalit movement, women adherents and members of the communist movement, the socialist women — made to advance women’s rights as citizen in the new republic. They stayed out of politics, working around mostly upper-caste homes and neighborhoods, but also slowly but steadily engaging in the everyday practice of spreading hate against the minorities to those who they took under their fold, especially lower caste families (as Golwalkar advised them to do, in his Call to Motherhood). This was one way in which women were integrated into Hindutva through a kind of ‘maternal agency’. But it still might look like a puzzle why women would accept such a depleted vision of their worth — definitely, they are placed below and under men in the present and future communities of Hindutva — until one notices the deployment of the hate story against the Muslims.

This is an highly entrenched narrative, as we all know, at least 150 years old. The stories of Muslim invaders whose real booty seemed to be the women of the Rajput (read Hindu) communities have circulated both in formal and formal channels of learning. As a BA student of History, I remember how casually teachers would recommed R C Majumdar’s poisonous ‘history’ books as an easy way out for the exams. Of course students in Delhi University of that time learned quite something else, but this was common in the non-metropolitan universities.

The Amar Chithra Katha, as has been noted by scholars, was also a channel by which these stories reached the Indian middle-class. In the north, there were the Partition narratives of Muslim rape which bolstered these already-existing stories, and of course, the persistent claim of Muslims being partial to Pakistan and global terrorism, and so on. As feminist scholars have pointed out keenly, the fear of Muslim attacks against the bodies of Hindu women has a potent effect. Feminist research on Durgavahini, for example, this fear allows young women to project their frustrations against powerlessness at home on to the hate for Muslims. The argument that if only the danger from Muslims did not exist, Hindu women would be free, is at the core of the persuasion tactics employed by such organizations. These young girls are then encouraged to espouse a hideously violent and inflammatory discourse against the Muslims and to worship weapons as a public expression of their will to violence. Indeed, women’s agency is then directed precisely towards violence against women.

Meanwhile, the BJP creates an impression of being more ‘women-friendly’. The Mahila Morcha offers a chance for ‘housewives’ to enter politics in defence of the hindutva nation. Also, celibate women seem to command great influence in the Hindutva formation; and a steady connection is built at the organisational level between organised hate-mongering by women and its everyday dissemination through RSS women who are not in politics. The presence of a sizeable number of Hindutva women in important posts in the government is no sign of democratisation at all; rather, it is the transfer of logic of the Brahmanical family into public institutions, in which women can only be daughters working under the guidance of the father, in which they need to remain totally silent unless the father directs them to speak. That explains the silence of BJP women leaders in the government and in politics about the protest by the wrestlers against sexual harassment by a BJP bigwig in charge of their affairs. Despite the fact that they were once feted by the Prime Minister Modi himself.

In Kerala, however, the 150-year-old hate story did not have as much traction. Rajput princes and Muslim rulers looked equally distant and unreal (the reason why finding them in books that claimed to be ‘history’ was so shocking back in the 1980s) in a place where Muslims were known for their enterprise and anti-colonial bravery (no history of Malabar could deny that) and not for their conquests. The local myths we grew up with did not support the fear of Muslims, much to the contrary — for example the tales of the Robin-Hood figure of Kayamkulam in the 19th century, Kayamkulam Kochunni, which spoke of how he protected Hindu women on the roads. There were also tales of contests between Ezhavas and Muslims in the bazaars of Travancore around the latter insulting Ezhava women, but those tales were clear that the insults were rooted in the insidious order of caste prevalent then, and not just in Muslims.

The exception to this were the narratives of the Mappila Uprising, which have been used again and again to whip up communal anger in Malabar. I personally have something like the fear of the sexual marauder-Muslim in senior women of the oppressor-caste in Malabar who had memories of the event or experience of it. Therefore the story of the marauder-Muslim was equally matched by the response that the Mapplila protestors attacked largely their oppressors and the leadership did not sanction such violence against oppressor-caste women. The Muslim community of Travancore spoke up at even the most aesthetically-refined adaption of the hate-story, by the poet Kumaran Asan, eliciting an apology from him.

In twentieth century Kerala, the women who were oriented towards a Hindutva imagination were shaped through caste politics, mainly. The early decades of the twentieth century saw a refurbishment of the Brahmin-sudra consensus that was the bedrock of the intensely-dehumanising traditional caste order of janma-bhedam (difference by birth). Crumbling under the impact of oppressed-caste assertions of many sorts, the oppressed-caste communities responded with community reform initiatives.

Community reform leaders (mainly men) initiated a selection process by which the completely-ritualised everyday lives of the Brahmins and the servile position of the Nairs would be revised to meet the demands of modern life. Ritual observances and practices — aachaarams — were now confined largely to homes and places of worship. This produced a cultural formation which I call the ‘neosavarna’. In the neosavarna imagination, women were primarily associated with the home, and thus, with aachaarams. Thus the menstrual taboo, for example, was an aachaaram observed in all conservative oppressor-caste Hindu homes. Women were integrated into the neosavarna precisely through such practices.

The sacrifice of liberal freedoms by women of these organized communities was nothing short of a condition to partake of both the caste-capital as well as economic protection offered by the oppressor-caste community. Importantly, in the twentieth century, neosavarna women, just like women of other organized communities of the time, were bound to their communities not through fear of the Other, but through the committment seemingly accompanying birth.

In sum, the major device available to the Hindutva far-right to drive Hindu women into their fold was just not available widely enough in the twentieth century. However, by the end of that century, conditions were ripening for Muslimphobia. While the visible signs of wealth — the spatial dominantion — by oppressor-caste Hindus declined somewhat after the land reforms of the 1970s, Muslim migration to the Gulf countries increased their spatial presence. The palatial homes, new-style mosques, the increasing numbers of Muslim-sponsored institutions, coming up in both urban and rural areas, the new high-consumption lifestyles of Muslim families, the new clothing styles inspired by Malaysian, Indonesian, and Saudi Islamic modest wear — did unsettle many Malayalis, conservatives and progressives alike.

Such changes did not really drive more Hindu women into the Hindutva fold immediately — as mentioned above, it was the possibility of sharing caste-capital more than hatred of the Other that oriented them towards the neosavarna Hindu imagination. The celebration of Hindu glory in the speeches of Kerala’s many Hindu preachers and god-persons who drew the monied Malayali upper- and middle-class neosavarna (which by now was also attracting women of the upwardly mobile sections of the oppressed castes as well) began to slowly be laced with exhortations to return to aacharam-ised lifestyles.

It was in 2009 that the Hindutva rightwing hit upon ‘love jihad’ as a weapon to bring the hatred of Muslims into Kerala. Gradually, it obtained soft acceptance among the progressive sections of Malayalis as well. This was possible only through strong support for the narrative by the organized Christian church, especially the oppressor-caste Syrian Christians. Though the state authorities did deny it happening on an organized scale, it was undeniable that young people were increasingly choosing the marry across caste/religious divides, seeking partners on their own — especially, young women were defying family and community authorities in their choices. This happened due to a confluence of many socio-economic shifts in Kerala since the 1990s — including the massive expansion of higher education, the coming of globalized mass media, expanding digital spaces and access to the Internet, as well as the deterioration of organized communities as social institutions capable of renewal under changing economic conditions. However, the easy way out was to find a Muslim conspiracy and outsource the violence to the Hindutva far right.

Much has been said about the CPM’s Chief Minister V S Achuthanandan’s thoughtless remarks about the Muslim community as a ‘breeding threat’, but their real failing was in their lukewarm attitutude towards the mushrooming of far-right spaces of coercion and punishment in Kerala, where, apparently, young Hindus who had transgressed community boundaries in their choice of partners were forcibly brought, or tricked into, violent ‘re-education’. Two women told the court that they were subjected to torture in an effort to make them leave their non-Hindu partners. Yet very little was done to tackle the root of the problem — the focus was all on how a Muslim man, Shafin Jahan, was out to seduce an Ezhava-born woman, Hadiya. Indeed, no wonder by 2022, utterly-provocative Durgavahini marches with young, often underage, girls brandishing weapons which were unknown here, began to be taken out . But even though the state has not learned much, progressives in social media see the danger now, thankfully. An outcry on social media led to police action, but we do not know what else is being done. Criticising the police action, BJP State President K Surendran declared that the girls merely sought protection from ‘religious terrorists’. In other words, fear of the Muslim is now being used to integrate Hindu girls into the Hindutva formation here, as in other parts of India.

The significance of this must not be underestimated. Especially when one sees that even as early as 2018, even the ‘uprising of Sudra women’ that happened in 2018 against the SC judgment permitting women of menstruating ages to enter the forest shrine of Sabarimala was rooted less in the hatred of the Muslim and more in protecting aachaaram — in other words, protecting neosavarna women’s claims to caste-capital. The ‘Ready to Wait’ women were ready to even oppose the RSS which supported the SC judgment initially — in defence of their caste-capital, which accrued through the performance of such aacharam. This phase is clearly passing, judging from the boldness with which the Durgavahini march was held and defended, which signals a new confidence. This is corroborated by other incidents in which Hindutva women have declared the importance of carrying the marks of (high)Hindu belonging on their bodies — the red dot, sindoor, the sandal-paste mark on the forehead etc. to ward off Muslim men.

I think, therefore, that The Kerala Story‘s makers banked on this newfound confidence among the Hindutva adherents.

How should we respond to this insanity? I think we should use what we Malayalis excel at — our sense of humour. As a people who have lifted ourselves by our bootstraps from dire poverty to being one of the richest people in this country which has always pushed us into oblivion, we have created tools to defend ourselves — without violence. Denied the prospects of employment through systematic neglect by the Centre, we sought opportunities in the global job market. Once humiliated as an ‘overpopulated’ state, we turned it around, and the whole world noticed. Among the social science disciplines, it was not ‘Indian History’ which gave us visibility (as I found out as a teenager in the 1980s); it was in the global Development Studies in which Kerala found recognition. Remember, this is despite the fact that Kerala never managed to break out of the colonial shaping of agriculture, never could find a vision of industry viable in an ecologically-fragile state.

So we should tear The Kerala Story, this already-laughable piece to bits through our laughter.

Yes, for once, the Malayali troll armies on social media that are not of the far-right Hindutva have a job cut out for them. Please chop up this miserable whining lie into tiny laughable bits — in ways that will forever enshrine the stupidity and dishonesty of its makers and actors for the never-ending amusement of posterity.

c. kafila.online