The party’s enviable performance in Bihar elections has escalated Owaisi’s confidence who has now set his eyes on Bengal and is bent on grabbing at least a fair share of the TMC-ruled state’s Muslim-dominated assembly constituencies

Dr Mehebub Sahana | Clarion India

AS the nail-biting Bihar assembly polls are over, the West Bengal assembly elections are a bull’s eye for all the political contenders. Scheduled in April-May 2021, the media stocks are skyrocketing with the analysis from political theorists, intellectuals, and commons, with the assumptions that Bihar elections might impact the upcoming Bengal polls.

From the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, West Bengal is a state of sheer interest for the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) to win due to several key factors connected to the national politics. After vanquishing the Congress through an outstanding success of 40% vote share and 18 MP seats in the 2019 Lok Sabha polls, BJP, the current ruler at the Centre, stands as the monumental challenge against Mamata Banerjee’s All India Trinamool Congress (TMC) in the upcoming assembly elections.

The Centre’s political move to enact the Citizenship Amendment Act in December 2018 has infuriated the masses and sparked a nationwide No-NRC movement. West Bengal being one of the epicentres for such national movements, the move has rattled BJP and sent them on the back-foot. The coronavirus outbreak, however, acted as a positive catalyst for the ruling party easing the rat race for them.

While CAA and NRC movements catapulted significant resentment from the masses, capturing the West Bengal assembly became a real challenge and threw cold water on the enthusiasm of BJP for a while. Covid-19 resulted in many unprecedented turns nationwide and West Bengal was no exception. The burgeoning economic crisis, politicising virus control, incalculable upshots of lockdown, corruption in relief distributions, etc. have all provided opportunities for political blame games between BJP and Trinamool Congress in the upcoming 2021 polls.

After BJP’s victory in the recent Bihar elections, it’s a neck-and-neck fight for both BJP and TMC. Meanwhile, the emergence of AIMIM party led by Asaduddin Owaisi as an underdog in the Bihar elections and surprisingly, winning 5 seats is no mean achievement. It created a different tension with a significant amount of attention as AIMIM’s wining of Muslim majority districts like Seemanchal areas situated on the Bihar-Bengal border and Malda, Uttar Dinajpur and Murshidabad of West Bengal are crucial seats in the elections.

Eventually, AIMIM’s victory over minority regions will seemingly unleash new political turns in the upcoming Bengal elections. The party’s enviable performance in Bihar elections has escalated Owaisi’s confidence who has now set his eyes Bengal and is bent on grabbing at least a fair share of the TMC-ruled state’s Muslim-dominated assembly constituencies.

This has made the Bengal polls an exciting battle of the ballots. While the AIMIM’s intrusion into Bengal election will keep everyone guessing, there are several exigent factors related to Muslims in Bengal that will play a strikingly major role in the assembly elections. Let us see at a glance what those crucial factors are and how critical they are:

Minority population and number game

Statistically, West Bengal is home to the highest percentage of Muslim population in India after Kashmir and Assam. The 2011 Census says that Bengal has 27.1% Muslim population and the districts like Murshidabad, Malda and Uttar Dinajpur have more than 50% Muslim population. Apart from these three districts, Birbhum (37.06%), South 24 Parganas (35.57%), Nadia 26.76% and North 24 Parganas (25.82%) also have minority community-concentrated districts.

A few blocks of Howrah, Hooghly and Purba-Bardhhaman are also in this list. Geographies with a populous minority have always played a determining role in the electoral demography in Bengal elections. So, Muslim-dominated assembly constituencies hold significant importance in impacting the state elections. After the power structure turned saffron at the Centre that endorses extreme Hindutva politics, Bengali Muslims were filled with anxiety, escalating identity crisis and impelling identity politics within the community.

Although the minorities believe that their position of being in servitude to the new government is obnoxious, they are thinking of alternatives at the same time. Any kind of healing factor, like a political hope, attracts their attention and AIMIM is grabbing this angle as a golden chance. Thus, utilising the Muslim sentiment and minority card, AIMIM can play an important role in West Bengal elections like they did in Bihar.

But a political twist exists as the Bengali language and culture are not as neutrally monolithic as Bihar. It’s possible to gain a victory in West Bengal but only an average amount of Muslim votes can be secured from Malda, Dinajpur and Murshidabad districts. To understand this political composition, we need to focus on the historical background of Muslim choice for Bengal politics.

Figure 1: Blockwise distribution of Muslim population in West Bengal (Census 201

Figure 1: Blockwise distribution of Muslim population in West Bengal (Census 201

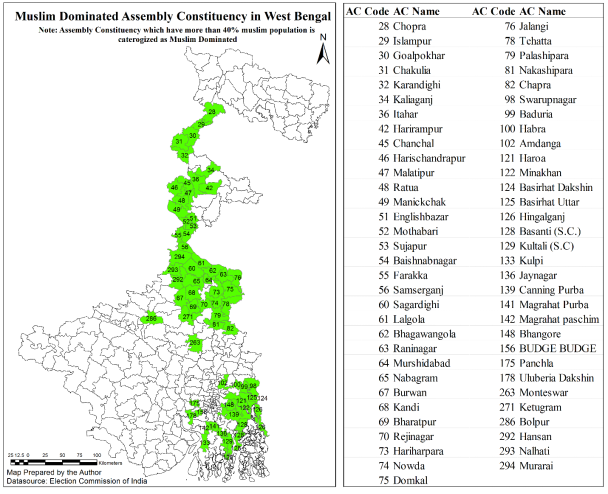

Initially, for decades, Congress benefited from the beginning of the Bengal assembly elections by the Muslim votes, specifically in the districts like Murshidabad, Malda and Uttar Dinajpur while CPIM had the strongest hold on the southern districts. Almost 90 to 100 of the 294 seats in the assembly were dependent on the Muslim votes where Muslim population is more than 30%. In 63 assembly seats, Muslim votes total more than 40% and without a huge amount of Muslim votes wining in these seats is very difficult.

For the last five assembly elections, dependency of these seats is an important game-changer for forming government in Bengal. However, in the pre-Mamata era, some of the minority- majority assembly seats were dominated by the regional parties like AIBF (All India Forward Bloc), RJD (Rashtriya Janata Dal), RSP (Revolutionary Socialist Party), CPI (Communist Party of India) and other small parties due to regional leadership.

Before Sachar report 2006, Muslims were not aware of their situation being entirely manipulated by decisions of the largest national parties like Congress or CPIM. They were, to some extent, hardly conscious of identity-based political participation. That’s why in the pre-Sachar period, minority voters could not influence the state elections. Polarisation and minority feelings started only during the post-Sachar period.

Figure 2: Blockwise distribution of Muslim Population (in %) and Muslim-dominated assembly constituencies (ACs) (Muslim population is > 40%) in West Bengal.

Districtwise number of minorities-dominated administrative assembly seats where the Muslim population is more than 40%

|

Districts |

Number of AC where Muslim population is more than 40% |

|

Purba Bardhhaman |

1 |

|

Dakshin Dinajpur |

2 |

|

Howrah |

2 |

|

Nadia |

4 |

|

Birbhum |

5 |

|

Uttar Dinajpur |

6 |

|

North 24 Parganas |

9 |

|

South 24 Parganas |

9 |

|

Malda |

11 |

|

Murshidabad |

14 |

|

Total |

63 |

What TMC does in 2011 and 2016 with minority votes

The Sachar Committee Report came out in November, 2006 just a few months after the Bengal assembly elections. The report stated that the condition of the Bengali Muslim minority is worse compared to any other Muslim communities of the country. Disagreement, disappointment, and resentment had spread like wildfire over the Muslim community in Bengal. Columnists, intellectuals, journalists, political theorists, and diverse professionals blamed the communist rule in Bengal not just across the nation but even in various international articles.

After this report was published, Muslim regional politics in Bengal was divided in two big wings—one was led by the Siddiqullah Chowdhury, president of the Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind’s West Bengal branch, while the Sunni Muslim group was shaped under the dominance of Furfura Sharif. Chowdhury formed the People’s Democratic Conference of India (PDCI) which is contesting under United Social Democratic Front (USDF).

A significant popularity in Muslim-dominated areas from the districts like Murshidabad, Birbhum and Bardhhaman, has been earned by Chowdhury while Toha Siddiqui has a captivating dominance over some places in north and south 24 Parganas, Howrah and Hooghly. Surreptitiously, Mamata Banerjee took this advantage by collaborating with Chowdhury and Siddiqui, earned her noticeable popularity in the Bengal Muslim community. Moreover, these two stalwarts from the minority community helped her to succeed in the Nandigram Movement also, which was a game-changer in her victory in the 2011 assembly elections.

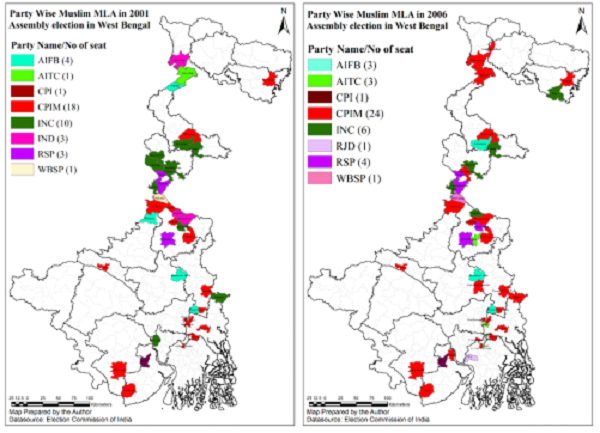

During the 2001 and 2006 assembly elections, CPI(M) came to power where they had 18 Muslim MLAs in 2001 and 24 MLAs in 2006, while others are mostly minority-dominated constituencies and were won by 5 or 6 parties, including the Indian National Congress.

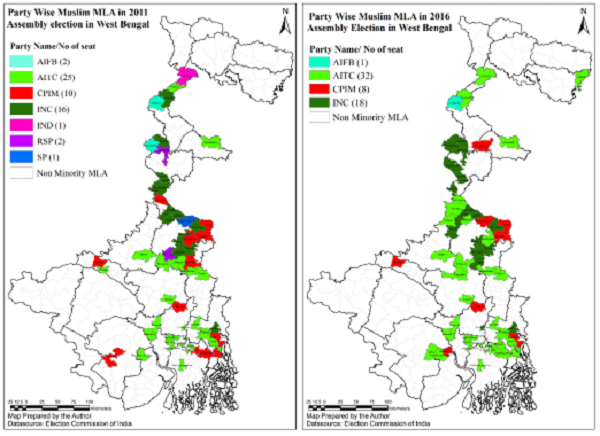

In 2011, Mamata Banerjee’s TMC emerged triumphant defeating the CPI(M) which had been in power for 35 years. In 2011, TMC own 184 seats in Bengal where 25 Muslim and more than 10 non-Muslim candidates won from the minority- dominated seats where in the 2016 elections, TMC was able to win almost 50 seats where 32 are Muslim MLAs from the minority-dominated constituencies, thus enabling the party to conquer as many as 211 out of 294 seats.

So, technically, Mamata Banerjee’s party had heavily benefited by minority votes in the last two assembly elections. TMC had collected the maximum minority-dominated seats by increasing the number of Muslim MLAs and with promises like, Imam Bhata, new madrasas and jobs for Muslims. This technique has enhanced TMC’s political strategy in the last two polls.

TMC is losing hold over minority votes

No doubt, in the last two elections, Muslims fully supported Mamata Banerjee’s TMC government, but gradually, the disappointment has been escalating among the Muslim community who are now seeking an alternative. That these Muslim votes would ever be reverted to the Congress or CPIM seems improbable as these two ideologies have been deemed to be unfit to the masses.

Mamata Banerjee announced that her party had fulfilled 90% of their promises for the minority community. However, Muslim voters, along with some of the popular figures, questioned the credibility of this statement as the Mamata Banerjee’s government has stopped giving recognition to new madrasas (academic) which was one of the promises made by TMC and top priorities for the Muslims.

In last few years, TMC has been unable to fulfil the recruitment process for the madrasa service commission and has failed to give jobs to the Muslim youths. Also, several issues have cropped up in allocating 10 per cent reservation for the minority community in the government. Their inability to generate sufficient employment did not go well with the minority community as the Mamata-led government used it as a trope to come to power in Bengal.

Also, TMC is facing a lack of a popular Muslim face, who could ideally represent the community who can douse discontent among the minorities. Siddiqullah Chowdhury and Toha Siddiqui are also witnessing a waning popularity within the minority community due to their little or no intervention in several issues triggering the minority sentiment.

Figure 3: Partwise Muslim MLA in the assembly election of 2001 and 2006 during the CPIM rule in West Bengal.

Figure 4: Partywise Muslim MLAs in the assembly election of 2011 and 2016 during the TMC rule in West Bengal.

Rise of BJP in border districts and North Bengal

In the 2016 assembly elections, BJP won only 3 seats and it had a 10.16% vote share from the total. If we compare the vote share of BJP for 2014 and 2019 Lok Sabha elections, we can find out a massive increase in its vote share from 16.8% in 2014 to 40.25% in 2019. If we analyse this path-breaking victory, we can obviously find out the rise of Hindutva politics in three key areas like Jangal Mahal, North Bengal and the areas surrounded by the holy city Nabadwip.

If we keep an eye on the 2019 election results, we can clearly foresee the indication that BJP has been more focused in border districts of Bengal for 2021 elections. Subsequently, there are several important repercussions impacting public opinion through the visits of the Prime minister Narendra Modi and the Home Minister Amit Shah, mostly in Bankura and Midnapur areas. They have been clear in their strategy to secure 100-120 seats from these border districts and 40-50 more can be possible if the vote-cutting strategy works in the central and south Bengal.

Figure 5: Distribution of winning parties in the 2016 assembly election in West Bengal and 2019 Parliamentary elections in India.

Rise of new Muslim politics and crucial factors in assembly polls

With the rise of BJP in India in the past 8 years, the minority politics is also shifting towards a community-centric politics due to fear and identity crisis. Now it’s a national debate within the minority community that the Muslim should have their own secular nationalist party or they have to continue with other mainstream secular and regional parties.

Within this debate, several small parties from different backgrounds, now seen as formidable forces, are trying to fulfil this political vacuum. Similarly, Bihar elections have revealed that with the Progressive Democratic Alliance (PDA) which has 8 partners and Owaisi’s AIMIM-led third front have proved to be kingmakers with more than 10% votes. Also, a similar phenomenon is noticeable in the Maharashtra and Assam elections where minority communities are searching for a secured, effective, and favourable alternative.

In other words, we can conclude that in the rising state minority politics in West Bengal, three important minority factors can influence the state elections. First, Owaisi’s AIMIM splitting of minority vote in some assemblies of Malda, Murshidabad and Uttar Dinajpur districts, will influence and can be an important factor in the Urdu- speaking Kolkata and Howrah.

But it won’t be an easy victory like Bihar because they don’t have an organisational framework like Bihar. Perhaps, AIMIM can be more damaging for the vote bank of the Congress rather than TMC because Congress seats in Bengal belong to Sujapuri Muslim-dominated areas.

The second striking factor is the rise of Pirjada Abbas Siddiqui who is much popular in Bashirhat, Hooghly, and Howrah. Recently, he has announced to contest in 44 seats from the Muslim-dominated seats in south Bengal forming his own party. Just two days ago, Congress’s Adhir Ranjan Chaudhuri visited his place for a discussion, hoping that if Pirjada Abbas Siddiqui allies with the Grand Old Party, it would surely be a big headache for Mamata Banarjee.

The third and important factor, and the crucial aspect will be sharing or cutting off votes between TMC, the Congress, and CPIM. However, BJP has already secured maximum votes in the Hindu-majority western districts like Bankura, Purulia, Jhargram, both Midnipur and northern districts like Darjeeling, Kalingpong Jalpaiguri and Alipurduar. Typically, TMC and Left will play the most stationary role in these areas.

Now, apart from all these seats, the 90 to 100 seats where minority votes could be shared would amount to more than 30% seats in the 294-member Bengal House. If all these factors area taken as reactions of the minority community, it would automatically favour BJP with an assurance to secure 30-40 seats from Muslim-dominated constituencies. This without doubt would be a big blow and matter of concern for the ruling TMC government.

_____________

Dr Mehebub Sahana is Research Associate, School of Environment, Education & Development, University of Manchester, United Kingdom. The views expressed here are author’s personal.