Akhtar Mahmud Faruqui

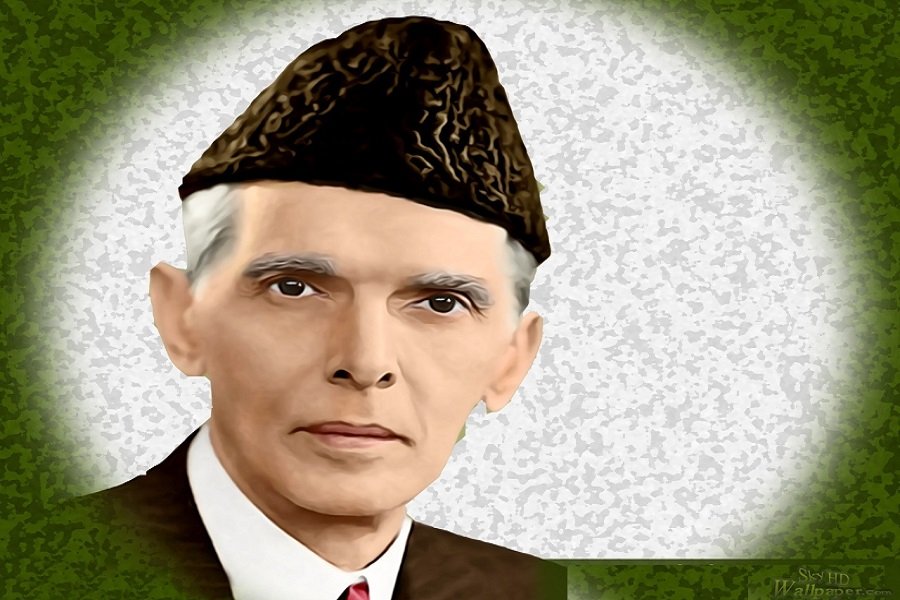

MARCH 23rd, 1940 marks a singular milestone in the history of Muslims of South Asia. It was truly a momentous occasion. At Lahore’s Manto Park, Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah rejected a permanent communal minority status for Indian Muslims. Instead, he demanded full-fledged nationhood and a separate country.

It proved a defining moment. Accounts of the meeting are graphic. The Quaid’s voice resonates in the sprawling Park to the accompaniment of hushed silence of the overflowing assemblage. “The Musalmans are not a minority. The Musalmans are a nation by any definition,” he unequivocally claims.

The Quaid speaks in his clipped British accent. His King’s English is beyond the comprehension of the teeming multitude. But they are all-attention. He is trusted as a champion of Muslim cause.

The Times of India readily conceded that “such was the dominance of his personality that, despite the improbability of more than a fraction of his audience understanding English, he held his hearers and played with palpable effects on their emotions.”

Yet, the speech marked a paradox in his political career. In 1916, the Quaid was hailed as the Ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity, a supporter of Indian nationalism. A quintessential Victorian gentleman, the Lincoln Inn barrister was steeped in European thought. He studied law in London, admired Prime Minister William Gladstone and Abraham Lincoln, and regarded as the Muslim world’s answer to Thomas Jefferson. Mixing religion with politics was not his forte.

What transpired in the intervening period of 1916 to1940 for his change of heart to alter course?

The Pakistan Resolution of 1940 and its subsequent adoption by the Muslim League was an answer to the Indian National Congress’s consistent attempts to deny the Muslim community a political entity of their own, according to eminent historian Prof Shariful Mujahid. The crux of the issue was whether India was a uni-cultural, bi-cultural or multi-cultural state.

The controversy, Prof Mujahid explains, began on September 18, 1936, when Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru made the outrageous claim, “The real contest is between TWO forces – the Congress which represents the will to freedom of the nation, and the British Government in India and its supporters who oppose this urge and try to suppress it. Intermediate groups, whatever virtue they may possess, fade out or line up with one of the forces…”

Nehru’s two-force dictum was not a stray declaration. Mr Jinnah’s response to this onslaught came at the Calcutta Muslim League meeting. “I refuse to line up with the Congress. I refuse to accept this proposition. There is a third party in this country and that is Muslim India … We are not going to be camp followers of any party,” Jinnah declared.

The March 23rd Pakistan Resolution formally declared India as bi-national and bi-cultural. In August 1947, the sub-continent split into two countries – India and Pakistan.

Seventy-eight years later, on this day, the stock-taking continues to reappraise the past in the light of the present. Ungrudgingly, the irritants are several and formidable. But the successes are many and furnish proof of a country on the march: Surely, the 1940-winter of despair seems to have given way to a spring of hope in post-Independence Pakistan.

Some milestones stand out: The United Nations has named its prestigious research institute in Italy as the Salam International Center for Theoretical Physics; nuclear engineers draw energy from the heart of the atom, and Alhomdolillah, without a Chernobyl or Three Mile Island accident; women excel in the role of Nobel Prize winners, prime ministers, ambassadors, Oscar-winning producers, fighter pilots, and diplomats irrepressibly raising their voice at the United Nations for the Kashmir cause; Dawn, Herald, Express Tribune, Daily Times and Newsline conform to quintessential journalistic excellence as a multiplying fraternity of TV channels presents the national perspective on different issues; LUMS, NUST, GIK, IBA and other universities impart momentum to the diffusion of higher technical skills in the country; the Supreme Court boldly plays its role in bringing plunderers and looters to justice; Sadequain paints more murals than Michelangelo and Diego Rivera combined; Arfa Abdul Karim Randhawa becomes the youngest Microsoft Certified Professional at 9; the Pakistan Army moves into the northern Waziristan tribal region, an area treated as no man’s land for centuries by the British, India and the Russian Empire, and stamps out terrorism. The soldier-to-officer casualty ratio at 12 to 1 is reported as the highest in military operations since 9/11.

The social transformation accompanying these successes is the focus of western media: ‘American fast-food and Western fashion outlets take Pakistan’s growing middle class by storm, defying stereotypes about a conservative Muslim country plagued by violence… New malls offer wealthy clientele in Karachi the chance to lunch on an American burger, buy French cosmetics, shop for cocktail dresses, sip an afternoon cappuccino or wolf down a cinnamon roll.

‘Lahore fires the imagination of writers, artists and thinkers during the annual literary festival when large crowds fill the halls of the Alhamra Art Center to listen to lilting recitals of Urdu and English poetry, and to delight in classical dance and music. Luminaries from Pakistan’s growing club of young internationally-renowned writers turn out to read from their novels, along with eminent authors from abroad like British historian William Dalrymple.’

Across an ocean and a continent, the creative impulse gathers steam. Dr Mark Salman Humayun, co-director of the USC Eye Institute in Los Angeles and grandson of the Quaid’s personal physician Dr Ilahi Bakhsh, receives America’s highest award for technology achievement from President Obama; Pakistani-Americans in the Silicon Valley, earn the title of a ‘model minority’, and win accolades for contributing to what Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee describe as “The Second Machine Age”. A Forbes story acknowledges that Pakistan is among a dozen countries which are seen as birthplaces of some of the most successful Silicon Valley companies.

Dr Nergis Mavalvala, a Pakistani-American professor at MIT, is a member of the Nobel Prize winner LIGO team that explores new vistas to resolve the mysteries of our universe. Dr Faisal Cheema conducts cutting edge research at the Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Heart Institute to study the possibility of using hearts from donors after circulatory death. Besides, many doctors, engineers, academics, and entrepreneurs impact the American scene. Pakistani-Americans are generally better educated than average Americans. They are generous and charitable. Of late, the community is not inclined to exclusively support impoverished folks in Pakistan, instead several groups have emerged to help neighbors in America in their hour of need. The local Mosque is no longer just a place of worship. It has started reaching out to the outside to make a positive impact in the mainstream.

These successes are in consonance with the vision and drive of the founder, Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah, though some disconcerting trends are a cause of anxiety. Dismal governance, along with larcenous leadership, has certainly bred despondency today.

In these troubled times calling for tolerance, Pakistanis need to heed Jinnah’s first speech to the Constituent Assembly delivered on 11 August 1947. It is a seminal speech in the history of the country.

“You are free; you are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to your mosques or to any other place of worship in this State of Pakistan. You may belong to any religion or caste or creed – that has nothing to do with the business of the State . . . We are starting in the days when there is no discrimination, no distinction between one community and another, no discrimination between one caste or creed and another. We are starting with this fundamental principle that we are all citizens, and equal citizens, of one State. “

One hopes today’s irksome problems prove solvable with time. Faiz Ahmad Faiz’s famous lines

Ye daagh daagh ujaalaa, ye shab-gaziida sahar

Vo intizaar thaa jis-kaa, ye vo sahar to nahiiN,

are often hummed to express collective anguish. Besides being a poet, Faiz was an eminent journalist and respected in his role as Editor of Pakistan Times. He wrote many insightful pieces. Little is known of an editorial that he wrote on the dream of Pakistan on the eve of March 23rd. It is an edifying review of conditions then that are strikingly similar to those of contemporary Pakistan – wily individuals frustrating the strivings and march of the majority. The concluding paragraph sheds pessimism and breeds optimism, identically as do contrasting conditions in Pakistan today: This is how he sums up his editorial:

“There is nothing to be discouraged about. Individuals, many of them distinguished in rank and tested in previous struggles, failed us miserably in the fight for Pakistan. The failures that we have witnessed and shall continue to witness in the fight to realize the dream that Pakistan stands for HAVE ALSO BEEN and WILL BE failures of individuals. Pakistan came IN SPITE of Khizar, and its PEOPLE WILL PROGRESS in spite of his successors.”

The foremost challenge today is to inspire national self-belief and self-esteem, and to stage a comeback on the international stage, to rediscover Jinnah’s spirit and vision which animated the Pakistan Movement and the founding of the nation. The documentary Mr Jinnah: The Making of Pakistan marks an effort to serve this all-important purpose.

The movie is a labor of love of Dr Akbar Ahmed, author, poet, filmmaker, playwright, and the leading light of dialogue of civilizations today. As the Ibn Khaldun Chair of Islamic Studies at the American University in Washington, DC he has emerged as the most balanced, learned and original interpreter of Islam in its engagement with the non-Muslim world. “It is hard to exaggerate the importance of this work…at a time when myths and fantasies still stir up corporate fear between our communities,” says Dr Rowan Williams, former Archbishop of Canterbury.

Dr Ahmed spent a decade creating and completing the Jinnah Quartet, which included Jinnah, starring Sir Christopher Lee and the documentary Mr Jinnah: The Making of Pakistan.

A special feature of the documentary, in the words of Dr Akbar Ahmed, is that it relies entirely on people who either knew the Quaid personally or were his contemporaries. In it we have prominent Pakistani, Indian, and British figures and were fortunate to obtain some historic interviews including that of the Quaid’s only child, Dina Wadia.

The candor and revealing views of the main actors of the critical period dispel the cobwebs that often plague the mind of students of history. Thus Jinnah’s critic Rafiq Zakaria, a former member of the Indian National Congress party and the father of Fareed Zakaria, the host of CNN’s GPS, laments “the most tragic moment in India’s history” as being the moment when, in 1946, Nehru rejected Jinnah’s proposal to explore safeguards for Muslims within India.

Zakaria is not a fan of Jinnah, but he cannot help admiring him, “Because of his brilliance, because of his cleverness, because of his incorruptible style of functioning, he was highly respected. There’s no denying that.”

Dina Wadia, the Quaid’s daughter, reflects on Jinnah’s family life and remembers her mother with great affection, “She was young and beautiful, very, very intelligent, very bright, loved beautiful things, and she was a humorous, fun person” and comments on the unhappy marriage of her parents: “Well, what happened was that he was a very, very busy man. He had all of his cases, he had a living to make, and then he had politics. Maybe he wasn’t able to give her the time that she should have had.”

The Quaid’s marvelous sense of integrity comes shining through when Zeenat Rasheed, the daughter of Haji Abdullah Haroon, tells him she and her female friends, dressed in different burqas each time, had cast fake votes for him:

“I’m very sorry you did that, because I have no intention of getting Pakistan in that way. I want it to be a fair election. And I’m sorry that you did that. And I would like you to go back and remove those three votes from the voters’ list, because you have no right to do it.”

One of the last interviews is that of Mike Wickson, Jinnah’s navigator, who flew the Quaid in 1948 from Quetta to Karachi on his last journey. He leaves us with an endearing image of the Quaid in the final hours of his life:

“He was helped aboard…And it so happens I was looking directly at Jinnah as he was propped up on his pillows. And he obviously saw the concern on my face, because he gave me the most wonderful smile, a smile I shall never forget. And it was a smile that said, don’t be concerned, all is well and all will be well.”

Finally, we hear Jinnah’s stirring words to the Constituent Assembly in 1947 which have APPEARED and DISAPPEARED as different governments attempted to create Jinnah in their own image, “You may belong to any religion or caste or creed — that has nothing to do with the business of the State …”

“It is crucial,” says Dr Akbar Ahmed, “that we remember the Quaid for who he was, which will help us determine how we understand and interpret his vision for Pakistan. This film can help us do that.”

(Akhtar Mahmud Faruqui is the editor of Pakistan Link.)