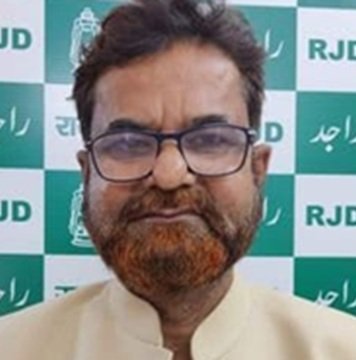

Syed Anwar Hussain

THE 17th of October is near. This is the day, recognised worldwide, when Sir Syed Day is celebrated with great enthusiasm at Aligarh Muslim University and across the globe. Sir Syed is remembered in many ways: seminars are held in his honour, his companions are commemorated, literary gatherings are arranged, and connoisseurs even organise qawwalis (a form of devotional music of the Sufis). But the central attraction of all these “memorial events” remains the Sir Syed Dinner.

Here, both current students and alumni—dressed in elegant sherwanis or suits—proudly display their deep attachment to their alma mater and to Sir Syed himself. At the conclusion of the celebrations, with passion and fervour, they joyfully recite Urdu poet and the son of the alma mater, Majaz Lucknawi’s famous verse:

“Yeh mera chaman hai mera chaman, mein apne chaman ka bulbul hun”

(This is my garden, my garden, I am the bulbul – nightingale – of my garden)

The children of Sir Syed do not recite these lines idly. In their tone, rhythm, and the music rising in the background, there glows the same conviction that one hears in the testimony of a new Muslim proclaiming: “There is no god but Allah, and Muhammad is His Messenger.”

But how can one explain to them that the garden they speak of now belongs to history? The alma mater they lovingly call by a variety of names like “my garden, Sir Syed’s garden, his paradise, his boulevard” has withered. Its trees and leaves are turning yellow. The autumn of decay hangs heavy in the air: its culture is dying, its traditions fading into forgotten tales, its walls crumbling, its roofs collapsing. If only you could understand that the garden of nightingales you claim to belong to, in this anthem, has lost its sweetness more because of elements amongst you than because of outsiders. If only you could understand that the garden of nightingales you claim to belong to has lost its sweetness more because of elements among you than because of outsiders.

This university, once hailed as the “Oxford and Cambridge of the East,” is now in decline. Once an international institution with students from over three dozen countries, it is shrinking into a regional one. Once it held the stature of an all-India university, now it is largely confined to Uttar Pradesh and Bihar.

Students once known for their dress, manners, and refined speech are losing their distinctiveness. At times it becomes difficult to distinguish an AMU student from one at a local degree college.

Once, fluent and elegant Urdu was the hallmark of both students and teachers. Even in casual conversation, linguistic delicacy was valued, and mistakes corrected. Today, careless speech—an unpolished mix of Hindi and Urdu, oblivious to pronunciation or grammar—is worn as a badge of pride, even as they continue to call themselves the “nightingales of Sir Syed’s garden.”

The university once had a culture where seniors would not even share tea with juniors out of principle. Today, stories abound of seniors exploiting their influence with wardens and provosts, taking thousands in bribes each month for hostel admissions.

The Students’ Union has been suspended for nearly a decade. Vice Chancellors, terrified of it, make yearly promises of elections, only to break them. This year again, elections are promised for December. But year-end is exam season—how can elections and exams take place together? Even if elections are held, the union will dissolve by April due to final exams. As Iqbal said:

“Aa ke bethe bhi na the keh nikale gai.”

(Hardly had they seated themselves when they were dismissed)

The administration fears elected leaders but cosies up to unelected, self-styled representatives—the sherwani clad sycophants—silencing them with perks. This vacuum has destroyed true leadership. Genuine, eloquent voices with character are vanishing, replaced by extortionists who take commissions from contractors and exploit poor workers by demanding bribes equal to a month’s wages.

And what of the teachers? Once, AMU had professors of international fame—scholars as well as administrators. Today, the university is filled with professors, heads, deans, and directors, but their stature rests more on their CVs than their classrooms. Their résumés list dozens of papers, but how many appear in reputable journals? A study of this alone could merit a PhD. If an international test were held to measure their competence, several of them would face demotion. Ironically, the more certain their demotion, the closer they are to the administration.

Education standard has fallen so low that neither teachers want to teach, nor the students want to learn. Attendance rules are a farce—students with even 30% attendance get their results released after protests. Some pass exams without attending a single class, aided by student “leaders.”

There are still capable teachers, but many have withdrawn in silence—teaching only those who wish to learn, ignoring the rest. Thanks to them, AMU manages to hold on to some ranking.

The phenomenon of declining standards among staff, and the earlier selection of Tariq Mansoor as Vice-Chancellor, serve as a case study. Everyone in Aligarh knew of his academic and moral standards, as well as his close ties with the son of former Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Kalyan Singh. Yet teachers and alumni overwhelmingly supported him, hoping for personal favours.

It is not only the standards of the students that have fallen; the moral standards of teachers have declined as well. During the centenary celebrations, despite strong opposition, the administration invited Prime Minister Narendra Modi as the chief guest. Shockingly, even prominent professors—once, and still, regarded as belonging to “Islamist” and Tablighi circles, known for frequently quoting Maulana Maududi and Maulana Ilyas Saheb—welcomed him warmly and urged others to do the same. Such moral compromise was rare in the past.

In earlier times, when buying loyalties through bribery was unthinkable, the AMU Students’ Union produced fearless and articulate leaders, writers, and poets such as Muhammad Ali, Shaukat Ali, Hasrat Mohani, Dr Zakir Husain, Basir Ahmad Khan, Javed Habib, and Azam Khan who boldly challenged and confronted governments and stood against their unfair polices. Vice-Chancellors, too, were once respected figures of national stature. Today, they appear small, timid, and subservient to district authorities.

The institution once known for fostering an ideal relationship between teachers and students now suffers from broken trust and strained relations. Decisions are imposed on students without consultation; protests are crushed under police boots. When repression fails, empty promises are offered to end sit-ins—only to be broken later.

“Is ghar ko aag lag gai ghar ke chiragh se”

(The lamp meant to illuminate the house eventually set the house on fire)

____________

The author is a former president of AMU Students Union. The views expressed here are author’s own and Clarion India does not necessarily share or subscribe to them.