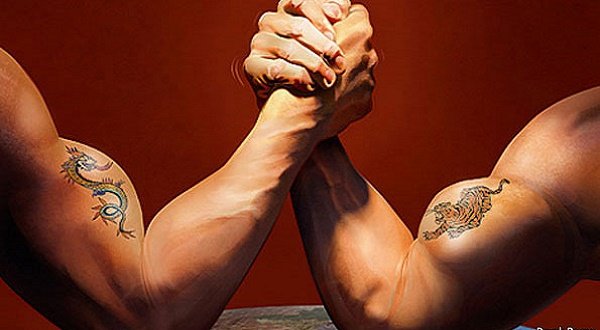

India’s GDP is currently less than a quarter of China. The Chinese economy’s growth rate last year was 7.7 percent while India’s grew at only 4.4 percent. Yet in the long run India could outshine China in the race for the leadership of Asia

GWYNNE DYER

[dropcap]S[/dropcap]oon after winning an absolute majority in the Indian parliamentary elections, prime minister-elect Narendra Modi promised “to make the 21st century India’s century.” If he can avoid tripping over his own ideology, he might just succeed.

“India’s century” is a misleading phrase, of course, because no country gets to own a whole century. It wasn’t ever really going to be “China’s century” either, although China is a huge country whose economy has grown amazingly fast over the past three decades. What Modi meant was that India, the other huge Asian country, may soon take China’s place as the fastest growing large economy – and it might even surpass China economically, in the end.

At first glance this seems unlikely. India’s GDP is currently less than a quarter of China’s although the two countries are quite close in population (China 1.36 billion, India 1.29 billion). Moreover, the Chinese economy’s growth rate last year, although well down from its peak years, was still 7.7 percent, while India’s grew at only 4.4 percent.

But China’s growth rate is bound to fall further for purely demographic reasons. Due partly to three decades of the one-child-per-family policy, the size of its workforce is already starting to decline. Total population (and hence total domestic demand) will also start to shrink in five years’ time. And this doesn’t even take into account the high probability of a financial crash and a long, deep recession in China.

India’s growth rate has also fallen in recent years, but for reasons like corruption, excessive regulation and inadequate infrastructure that are a lot easier to fix. And the reason that Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) won by a landslide was precisely that voters thought he would be better at overcoming these obstacles to growth than the worn-out and deeply corrupt Congress Party.

Modi did not win because a majority of Indians want to pursue divisive sectarian battles that pit Hindus against India’s many minorities, and especially against Muslims. That has always been part of the BJP’s appeal to its core voters, but its new voters were attracted by Modi’s reputation as the man who brought rapid development to the state of Gujarat, which he has ruled for the past thirteen years. They want him to do the same thing nationally.

They over-estimate his genius: Gujarat has always been one of India’s most prosperous states, and the local culture has always been pro-business. It was doing very well even before Modi took power there. Nevertheless, he might well be able to fulfill the hopes of his new supporters, for he arrives in New Delhi without the usual burden of political debts to special interests.

The BJP’s absolute majority in parliament means that Modi will not be constrained by coalition allies like previous BJP governments. This could lead to a leap in the Indian growth rate if he uses his power to sweep aside the regulations and bureaucratic roadblocks that hamper trade and investment in India. He also has a golden opportunity to crush the corruption that imposes a huge invisible tax on every enterprise in the country.

Unfortunately, his extraordinary political freedom also means that he will find it hard to resist the kind of sectarian (i.e. anti-Muslim) measures that the militants in his own party expect. He cannot use the need to keep his coalition allies happy as an excuse for not going down that road. Nobody knows which way he’ll jump, but it might be the right way.

Even some Muslims in Gujarat argue that Modi has changed since he failed to stop the sectarian riots that killed around a thousand Muslims there in 2001. Moreover, the election outcome makes it clear that a considerable number of the country’s 175 million Muslims must actually have voted for him. If he can keep his own hardliners on a short leash, everybody else’s hopes for a surge in the economic growth rate may come true.

What might that mean over the next decade? It could mean a politically stable India whose growth rate is back up around 7 or 8 percent — and a China destabilized by a severe recession and political protests whose growth rate is down around 4 percent.

While neither political stability in India nor political chaos in China are guaranteed in the longer run, by 2025 the demography will have taken over with a vengeance. China’s population will be in decline, and the number of young people entering the workforce annually will be down by 20 percent and still falling. India’s population will still be growing, as will the number of young people coming onto the job market each year.

That will give India a 3 or 4 percent advantage in economic growth regardless of what happens on the political front. In the long run both countries may come to see their massive populations as a problem, but in the medium term it looks increasingly likely that India will catch up with and even overtake China in economic power.