BOOK REVIEW

Dr Ubaid Iqbal Asim’s book documents a fascinating account of the history of the small, peaceful town in Uttar Pradesh

M Ghazali Khan | Clarion India

LOCATED approximately 150 km (93 miles) away from New Delhi, Deoband is a small and peaceful town in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh. However, despite hostile propaganda against it in the post-9/11 era — first by Western agencies and later echoed by some Hindutva organisations — Deoband remains remarkably non-sectarian and harmonious.

Except for a disturbance in 1992, during which six or seven individuals, all of them Muslims, were killed in a police shooting amid a highly charged communal atmosphere following the demolition of the Babri Mosque, Deoband has never witnessed violent intercommunal strife — not even in 1947, when much of the Indian subcontinent was engulfed in a communal frenzy and widespread violence. Such is the history of this town that when freedom fighters — mostly clerics from Darul Uloom Deoband — formed an Indian government in exile in Afghanistan on December 1, 1915, during World War I, Raja Mahendra Pratap Singh was appointed its president.

After 9/11, the West, particularly the United States, acted as if Islam had just been discovered. Taking a cue from the Bush administration at the time, Hindutva supporters also started behaving as if they had never heard of Islam or Muslims before. In the wake of the burning of the Sabarmati Express, when a Hindutva leader was asked why Muslims were being massacred instead of taking action against the real culprits, he justified the mass killings by arguing that no one had objected to the Bush administration’s bombing of Afghanistan.

In the highly Islamophobic atmosphere of the non-Muslim world and under the BJP-led government in India, how could Deoband — often, albeit without solid reason, considered a symbol of violent Islamic fundamentalism — be spared? Unfortunately, several follies of the Taliban government in Afghanistan, which claims to follow the Deobandi school of thought, both during their first regime and their current de facto rule, have provided additional fuel to vested interests seeking to maintain a tense atmosphere.

Unaware of Deoband’s history and failing to realise that ‘Deoband’ is not an Islamic name, in 2017 the newly elected BJP MLA of Deoband Brijesh Singh joined his party’s name-changing frenzy. He announced that he would propose renaming the town ‘Devband’ in the state assembly.

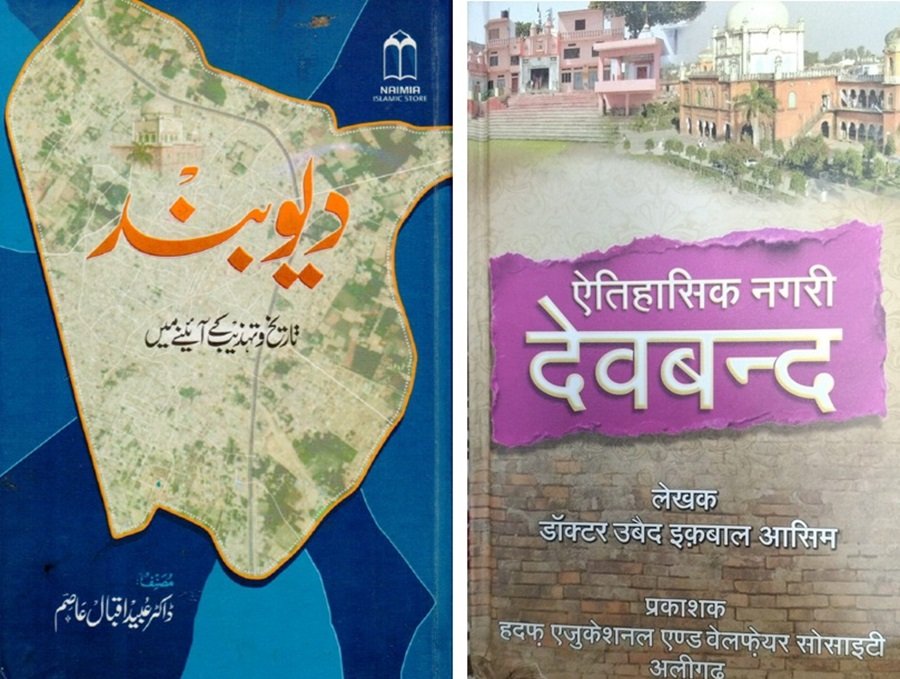

In such a situation, Dr Ubaid Iqbal Asim’s book Deoband Tareekh wa Tehzeeb ke Aaine Mein, along with its Hindi translation Etihasik Nagri Deoband, makes a significant contribution to documenting the town’s history — both the author’s and the reviewer’s hometown.

The books (512 pages in Urdu 560 pages in Hindi) are available at Kutab Khana Naimia, Deoband.

Writes Asim: ‘According to the priests of Devi Kund, an ancient temple in Deoband, and Hindu historians, this town is mentioned in the Mahabharata. Some priests of the temple have told this writer that the Mahabharata contains one or two verses in which Deoband is explicitly mentioned. Based on this, it can be inferred that the town existed even during the time of the Kauravas and the Pandavas.’

Asim refers to Munshi Nand Kishore, the author of Tareekh-e-Deoband (published in Saharanpur in 1868), who describes Deoband as being one thousand years old. He also cites Maulana Fasihuddin’s Jughrafia Zila Saharanpur (Saharanpur, 1866), which traces Deoband’s origins to a time before Vikramaditya.

Darul Uloom Deoband . (Photo Abdurrehman Saif)

The book presents several fascinating historical accounts. For example, it mentions Syed Ahmad Shaheed’s visit to Deoband in 1818 AD to recruit Mujahideen, during which he stayed there for ten days. The exact number of his recruits is unknown. However, according to the book, historical records mention the names of: ‘Four young sons of Muhammad Bakhsh — a gentleman from the fourth generation of Diwan Lutfullah — three of whom, Sheikh Buland, Maqsood Ali, and Syed Ahmad (also known as Sallu), were martyred in battle. The fourth brother survived and later passed away in Deoband. Others included Maulvi Fareeduddin, Syed Maqbool Alam, Maulvi Shamsuddin, Sheikh Rajab Ali, Maulvi Basheerullah, Ghazi Hafeezullah, Abdul Razzaq, and Abdul Aziz.’

The book provides brief accounts of each of these individuals. In a chapter dedicated to the freedom movement of 1857, along with a concise account of the role of the Deobandi ulema (scholars), it discusses the British government’s ruthless suppression of the struggle. It states:

‘Only in Deoband, 144 individuals were hanged. This scribe has personally seen the mango tree on which they were executed, once known as ‘sooli wala darakht’ [the gallows tree]. Sixteen individuals were sentenced to 10 years of imprisonment each, while 20 received three-year sentences. Thirty-four were fined, and several were forced to sign personal bonds to ensure future compliance. Seven were fortunate enough to be whipped and then set free. Three adjoining villages were burned down.’ (Quoted from Syed Mehmoob Rizvi’s book Tareekh-e-Deoband, p 186, Ilmi Markaz, Deoband, 1972)

In addition, the properties of all those who were even remotely suspected of participating in the uprising were confiscated. The Sheikhs and Syeds of Deoband were particularly affected by these actions of the British government. However, it is noteworthy that Hindus and Muslims fought side by side to free themselves from the yoke of British imperialism.

As Asim writes: ‘Although this town has been predominantly Muslim for ages, Muslims have never ignored their fellow countrymen on any occasion. On numerous occasions, they willingly accepted the leadership of Hindus.’

In a detailed chapter entitled “Azadi Ka Mansooba aur Deoband” (The Plan for Freedom and Deoband), the book provides insight into how Deobandi scholars strategised to expand the movement both within India and beyond. It discusses Gandhiji’s visit to Deoband on 29 October 1929, during which he was presented with ₹1,500 on behalf of its residents, as well as the deputation of students and teachers from Darul Uloom Deoband to various parts of the world, including Afghanistan, Turkey, and the Arabian Peninsula.

Regarding Maulana Mahmood al-Hasan, the renowned Deobandi scholar, the book states: ‘He was a great leader of his time… The uprising he sought to ignite was not meant for Muslims alone. He invited the Sikhs of Punjab, revolutionaries of Bengal, and members of the Ghadar Party to join his movement.’

The remaining gate of a 16th-century Khanqah or monastery. (Photo : Abrrehman Saif)

Maulana Mahmood al-Hasan was one of India’s foremost Islamic scholars and a key figure in the struggle against British rule. He had declared jihad against British colonial rule in India. After his arrest, he was sent to Malta, where he was imprisoned for four years. Those who performed his final rites reportedly observed several marks of torture on his body. However, this unsung hero of India’s freedom struggle never spoke about the suffering he had endured.

Asim writes: ‘Hindus and Muslims played a leading role in the anti-British movements of 1930, 1932, 1940, 1941, and 1942, enduring the hardships of imprisonment. After the country gained independence, a large number of freedom fighters migrated to Pakistan. Those who remained behind were mostly scholars associated with Darul Uloom Deoband, who refused to accept any government position or honorarium. They stated that they had not fought for personal recognition or material rewards but had done so as a religious duty, believing that their true reward lay with Allah.

‘One such example was the renowned scholar and freedom fighter Maulana Syed Husain Ahmad Madni, who served as the Sadar Mudarris (Head Teacher) of Darul Uloom. When he was offered prestigious honours such as the Padma Bhushan, Padma Shri, and Bharat Bhushan, as well as a seat in Parliament, he declined all of them, remaining steadfast in his principles.’

Unfortunately, despite its rich history, this town, where 70 percent of the population is Muslim, has always been treated unfairly — not only by the media but also by successive governments. Apart from two MPs and two MLAs, it has never had the opportunity to be represented by a Muslim in the state assembly or parliament. To add insult to injury, in the last municipal board chairmanship elections, the BJP-led state government went out of its way to impose a Hindu chairman on the town — someone who is not even a resident.

Strangely from 1948 until the 1960s Deoband and Kairana were grouped as a single parliamentary constituency. During this period, the Congress candidate, always a Hindu Rajput, consistently won in this electoral district. However, in 1964 Ghayur Ali Khan succeeded in winning the parliamentary seat on a ticket from Dr Ram Manohar Lohia’s Socialist Party, whose election symbol was the banyan tree. This unexpected experience was big shock for the then prime minister Indira Gandhi. Therefore, she merged Deoband with Haridwar, later designating it as a reserved seat for Scheduled Tribes.

The chapter, ‘Deoband Halqa Assembly’ is particularly interesting and offers many lessons for Muslims and fair-minded individuals.

Writes Asim, the long-time MLA Thakur Phool Singh could not stand in the midterm assembly polls due to his ill health. Therefore, Congress fielded another Thakur, Mahaveer Singh, as its candidate. His direct contest was with a well-known personality of the town and a candidate from Chaudhary Charan Singh’s Bharatiya Kranti Dal (BKD), Haji Jameel Ahmad Numbardar, who was equally popular among both Hindus and Muslims. However, general voters, especially Muslims, had hardly heard of Mahaveer Singh earlier. Due to his rustic tone, he struggled to attract voters.

It was widely believed that Haji Jameel Ahmad Numbardar would win the election. However, to everyone’s surprise, Mahaveer Singh secured victory by just a few hundred votes. His success was attributed to his Thakur background and the tireless campaigning of a dedicated Congress member and Municipal Board Chairman, Maulana Muhammad Usman. He played a crucial role in mobilising support, even at the cost of sacrificing his friendship and neighbourly ties with Jameel Ahmad Numbardar. Interestingly, Mahaveer Singh received the highest number of votes in areas previously considered strongholds of Jameel Ahmad Numbardar.

‘In 1974, Mahaveer Singh found himself in a direct electoral battle against his old friend Maulana Muhammad Usman, who had once sacrificed everything to help him secure a seat in the assembly. However, when Maulana Usman sought a Congress ticket for himself, Mahaveer Singh disrupted his plans, ultimately sacrificing their long-standing friendship. The Socialist Congress, led by Morarji Desai, which had emerged from within the Congress itself, seized the opportunity and offered Maulana Usman a ticket to contest the election under its banner. However, in the end, communal politics played a decisive role, and Maulana Usman was defeated by his own political disciple.’

Muslims form majority only in Deoband town. The rest is a Hindu majority constituency.

Asim continues: ‘In 1974, it became clear that the Deoband constituency had become a monopoly of a particular caste, willing to discard party loyalty, sacrifice every principle, and cross every standard of honesty to maintain its hegemony. Thakur Mahaveer Singh re-entered the political arena in 1984. This time, his opponent was a young politician, Badar Kazmi, the younger brother of Qamar Kazmi, Vice President of the All India Muslim Majlis.’

It was a four-cornered contest involving three Thakur candidates: Mahindra Tyagi from the Bhartiya Lok Dal, Ms. Shashibala Pundeer from the Janata Party (Chandra Shekhar faction), and BJP candidate Jaswant Singh, along with Badar Kazmi, a Muslim Majlis candidate contesting on the ticket of VP Singh’s Janata Dal.

It was presumed that this time the victory of a Muslim candidate was certain. According to Asim: ‘When the election results were declared, Thakur Mahaveer Singh defeated Badar Kazmi by a huge margin. An analysis of the voting pattern revealed that, once again, Muslim votes were divided [based on individual sympathies along party lines —reviewer), while our countrymen seemed intent on keeping a Muslim candidate away from this seat.’

Ancient Hindu temple Devi Kund. (Photo: Abrrehman Saif)

The sordid story did not end here. The same game was repeated in the 1989 parliamentary election. Writes Asim: ‘This time around Janata Party fielded Qamar Kazmi as its candidate. He was very close to Janata Party leader, and later Prime Minister of India, Mr V.P. Singh. He was popular as a serious worker and had considerable influence in Deoband and surrounding areas…’

‘The Congress party fielded a Thakur candidate against him who had no relationship with Deoband in the past… [Mahaveer Rana] was selected for his dominating personality in his [Rajput] community and had been a strong leader of Youth Congress. The fact is that Qamar Kazmi lost his winning election by a few votes due to his excessively gentle nature — so much so that it could be perceived as cowardice. This scribe is a witness to how Kamar Kazmi was fraudulently defeated in the seventh round of counting. Until the sixth round he was far ahead of his main rival…Two bundles of 50 votes each were put with Mahaveer Rana’s votes and an increase was shown in his votes. When Qamar Kazmi’s supporters protested, Mahaveer Rana’s guys became ready to turn vote counting into a battlefield. Seeing the worsening situation Qamar Kazmi was disheartened and showed his preparedness to withdraw but did not tolerate the possibility of blood-letting. Thus, Mahavir Rana was declared the winner by approximately fifteen hundred votes, and this seat, which was almost within Qamar Kazmi’s grasp, ultimately slipped away due to Mahavir Rana’s shameless behaviour.’

In this valuable book, the writer has not only provided an interesting history of this small but internationally renowned town — its population, its mohallas, the historical figures born and brought up here and their contributions in various fields, as well as its ancient and historical mosques and temples — but has also offered deep insights into its cultural heritage.

It is unfortunate that one or two chapters, primarily on Muslim scholars, have been omitted from the Hindi version. The author briefly covers the history of Darul Uloom Deoband, but readers should be aware that this book focuses on the history of Deoband town, not its renowned seminary. Consequently, it does not include any details about the capture of Darul Uloom by Jamiat Ulama-e-Hind, which was supported by the Congress government at the time. The Hindi version also contains photographs of historical places and institutions of the town.

There is no doubt that this is a good reference book on Deoband and also offers valuable insights into the current political scene in the country.