Critics and historians question the film’s impact on modern communal narratives

Mohammad bin Ismail | Clarion India

IN a largely polarised Indian society, the Hindi film Chhaava, which eulogises the Maratha warrior Chhatrapati Sambhaji Maharaj and demeans the Mughals, has caught the imagination of moviegoers. Within a week of its release, it earned over Rs 200 crore and is expected to surpass the Rs 500 crore mark soon.

The film portrays Sambhaji as both a brave warrior and a tyrant and depicts Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb as a cruel and Hindu-hating ruler. The film has stirred significant discussions in India, but does it fuel hatred and prejudice within society? Some Indian historians and conscientious individuals believe that such films are sowing discord and fostering misunderstandings between different religious and social groups.

However, the filmmakers assert that this historical film was reviewed by historians and expert researchers before its release. Despite several changes made during the censoring process, the film was required to clarify that its intention was not to defame anyone or distort historical facts.

Film critics point out that many warrior figures from Indian history, known for their bravery, courage, and self-sacrifice, are now being portrayed on the big screen by filmmakers. However, they are seen to be prioritising sensationalism over research, and religious extremism in the country is being exploited as an opportunity. Critics also argue that this film distorts historical facts.

It is true that the era of socially-driven cinema has passed, and while art films can generate capital, they do not bring in the same level of profits. In such circumstances, commercial films and those laced with sensational elements are the only ones that thrive, making huge profits. However, using a powerful medium like film to promote a specific agenda should not be encouraged.

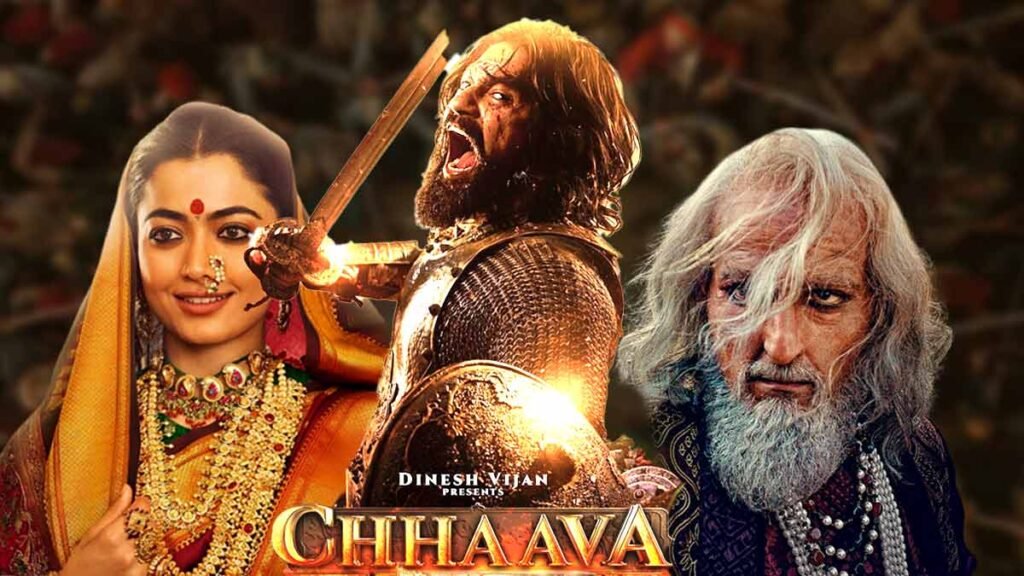

Films have also explored the wars, conflicts, and political rivalries between the Mughal rulers and various other states of different religions and nations in the subcontinent, often with great success. Chhaava is another action-packed historical film, directed by Laxman Atekar and released under the banner of ‘Mad Doc Films’. The story centres around the period of Maratha Chhatrapati Sambhaji. Bollywood’s Vicky Kaushal and South Indian film industry’s superstar Rashmika Mandanna have impressed with their performance. Critics have praised the last 45 minutes of the film, especially the emotional climax. Another key character is Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb, portrayed by Akshaye Khanna. The music for the film has been composed by AR Rahman.

In the past, Bollywood has produced films promoting the message of Hindu-Muslim harmony. A prime example of this is the song from the 1959 film Dhool Ke Phool: ‘Tu Hindu banega na Musalman banega, insaan ki aulad hai, insaan banega’ (You will neither become Hindu nor a Muslim; you are the child of a human, so will become human). Earlier, Bollywood films effectively countered the atmosphere of communalism and hatred. However, today, the situation is quite the opposite. If we look at the filmmakers and directors of today, they often argue that in the world of fiction and cinema, characters cannot be portrayed exactly as they are presented in authentic history books. But it is also crucial that historical facts are not distorted.

Chhaava is a film that depicts the events of the Hindu ruler Sambhaji’s reign after the death of his father, Shivaji Maharaj, his ascension to the Maratha throne, his conflict with Aurangzeb, and ultimately his death. The film explores Sambhaji’s attempts to prove himself as a worthy successor and his desire for Maratha dominance. His era was marked by constant battles with the Mughals, Siddhis, the Mysore state, and the Portuguese.

Maratha historians and writers have noted that Sambhaji, despite being a Hindu ruler, was responsible for the brutal killings and executions of several courtiers. After assuming power, he also executed key members of the Maratha royal court, which led to administrative instability and difficulties. As a result, a significant internal conspiracy arose against Sambhaji. According to these writers, Sambhaji was ultimately betrayed by his people. Some accounts suggest that Shivaji did not want to pass on power to his son Sambhaji due to his irresponsibility and immoral attitude.

In Chhaava, Sambhaji faces numerous challenges after the death of his most trusted commander and mentor, Hambir Rao Mohte. It is said that his death, caused allegedly by the immense pressure and torture from Aurangzeb in exchange for the renunciation of his empire and religion to save his life, earned him sympathy, particularly from the Hindu community.

Sambhaji’s death galvanised the Marathas to continue their resistance with renewed vigour. On the other hand, Aurangzeb’s relentless war against the Marathas weakened the entire Mughal empire. After Sambhaji’s death in 1689, Aurangzeb spent over a decade in the Deccan region, continually battling Maratha warriors until his own death.

While popular cinema is undoubtedly a major source of revenue, in recent years, Indian filmmakers have been criticised for deliberately employing certain formulas and adding sensational elements for commercial gain. In Chhaava, the character of Aurangzeb is portrayed in a highly negative and distorted light, and it seems the filmmaker has achieved his intended effect.

Shivaji founded his independent kingdom at a time when there were three Muslim sultanates in the western part of India: the Nizam Shahi of Ahmednagar, the Adil Shahi of Bijapur, and the Qutb Shahi of Golconda. These three sultanates were often at odds with each other, while the Mughal rulers from the north continuously pressured them to submit to their control, aiming to dominate South India. Amidst this turmoil, Shivaji raised the banner of rebellion by capturing four key forts in Bijapur, while Aurangzeb, with his powerful army, sought to quash this growing threat.

According to the renowned historian Robert Orman, Aurangzeb used all his power to crush Shivaji. However, the image of Aurangzeb being presented in Indian films is misleading. He is often depicted as a hardline Muslim and an enemy of Hindus who ordered the destruction of many temples and imposed restrictions on several Hindu festivals and rituals.

American historian Audrey Truschke, in her book on Aurangzeb, argues that it is incorrect to believe Aurangzeb demolished temples out of hatred for Hindus. She writes that the portrayal of Aurangzeb in such a manner is a result of British-era historians who fostered Hindu-Muslim animosity as part of the British policy of ‘divide and rule.’ Aurangzeb was a ruler who governed over 150 million people for 49 years, and under his reign, the Mughal empire extended almost throughout the entire subcontinent. Truschke further clarifies that ‘only a few temples were directly destroyed under Aurangzeb’s orders. There was no massacre of Hindus during his reign. In fact, Aurangzeb appointed Hindus to several important positions within his administration.’

On the other hand, Hindu historians and some religious figures describe Shivaji as a courageous and rebellious ruler, also praising his successor, Sambhaji Maharaj. A BBC report quotes Prof Nadeem Shah, who offers an alternative perspective on Shivaji. According to him, even after his return from Agra, the Marathas accepted the Mughal administration. Shivaji maintained diplomatic relations with Raja Jai Singh, and his ancestors had held positions under the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan. Shivaji’s grandfather had worked as a Mughal officer. Therefore, he argues, the relationship between Shivaji and the Mughals was not as hostile as it is often depicted today. However, there are differing views on how history is interpreted in India.

After the fall of the Bahmani Empire, it was divided into five parts. The Mughals first abolished the Nizam Shahi, followed by the Adil Shahi, and then the Qutb Shahi. Not only the Marathas, but also several other kingdoms, were under Mughal control. Aurangzeb also sought to bring Shivaji under his control as a mansabdar. Another historian, Kadam, disputes the claim that Shivaji’s grandfather was a mansabdar under the Mughals. He argues that Shivaji’s grandfather served under the Nizam Shahi and Adil Shahi rules and also protected the Nizam Shahi from Mughal domination. This is where the animosity between the Mughals and Shivaji’s family began.

Historians write that in an attempt to bring the Marathas into the Mughal fold, Aurangzeb sent Raja Jai Singh with an army to the Deccan. Raja Jai Singh succeeded in his mission, and Shivaji agreed to an accord with the Mughals, known as the Purandar Treaty. The agreement was named after Purandar Fort near Pune, which was conquered by the Mughals.

In recent years, religious extremism has risen to alarming levels in India. In Maharashtra, the government, working with a specific agenda, has removed content related to the history of the Mughals from school textbooks. The focus has shifted towards educating students about the Hindu ruler Shivaji and his empire. Indian intellectuals and critics of the government argue that countless monuments built during the Mughal era should not be erased from history based on religious grounds. They warn that an attempt to dismiss over three centuries of history will be damaging. The period of Mughal rule should be assessed based on its governance and contribution.

Historical accounts indicate that Sambhaji was no older than nine when he was taken as a political hostage by the Mughal empire, bound to adhere to the Treaty of Purandar. However, he managed to escape and eventually succeeded his father. He was a scholar, fluent in several languages, and became popular as a symbol of Hindu rule in India after his death. Sambhaji was born in 1657 at the Purandar Fort, the residence of Maratha Chhatrapati Shivaji. His mother died when he was just two years old. At the age of nine, Sambhaji was sent to live as a political hostage with the Raja of Amber. His father, Shivaji, had signed the Treaty of Purandar with the Mughals on June 11, 1665. According to historians, on May 12, 1666, Shivaji and Sambhaji appeared before Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb in Agra, where they were detained. After two months of captivity, they managed to escape.

During this period, Aurangzeb attempted to attack the Maratha empire from all sides. Sambhaji’s forces employed guerrilla tactics that confused the Mughal army, preventing Aurangzeb’s generals from capturing Maratha territories for three years. Sambhaji inherited his father’s system of government and, while continuing most of his policies, managed the state with the help of a council. It is said that he administered justice to his subjects and made significant progress in agriculture. However, some Maratha writers portray him as irresponsible and misguided — a view they dismiss by arguing that the historical sources we rely on are weak and that many reported events are either false or mere propaganda. Similarly, there are fictional and fabricated accounts about Aurangzeb that should not be exaggerated in films without thorough research. A glance at films in this genre over the years reveals titles such as Samrat Prithviraj (about King Prithviraj Chauhan of Ajmer), Maratha General Tanaji, Rani Padmaavat, Tashkent Files, Ghazi, and Sher Shah, among others.