To be sustainable, the strategy must not disturb the even tempo of life. Kashmiris are in a crisis that will not end soon. To begin with, it will not and cannot end without a settlement between India and Pakistan that also receives the people’s support. As Nawaz Sharif told visiting Indian journalists when he first became prime minister, the Pakistanis, Indians and Kashmiris must take a step back. Barring Mirwaiz Umar Farooq, none of the Hurriyat leaders show any inclination towards a compromise. One would have expected Kashmiris to press for a settlement, which cannot happen without compromise. But the very concept of compromise is unacceptable to Geelani and his associates

A G NOORANI

[dropcap]N[/dropcap]EARLY a quarter century after it was established, and after multiple splits, the All Parties Hurriyat Conference has decided at long last to formulate a considered strategy that is ‘sustainable’. One would have thought that this would have been its first task soon after its formation.

Its constitution, which was to “come into force from Aug 31, 1995”, set out its objectives; prime among them being “to make peaceful struggle to secure for the people of … Jammu and Kashmir the exercise of the right of self-determination in accordance with the UN Charter and the resolutions adopted by the UN Security Council. However, the exercise of the right of self-determination shall also include the right to independence … To make endeavours for an alternative negotiated settlement of the Kashmir dispute amongst all the three parties to the dispute”.

Those resolutions excluded, at the insistence of both Pakistan and India, the option of independence.

The Hurriyat’s leaders must descend from their perches.

The Hurriyat never sat down calmly to deliberate on strategy. If it has done so now, it is because its leaders were seen to have failed miserably in the crisis that engulfed Indian Kashmir since the killing of Burhan Wani on July 8, 2016. Shops were shut for months. Business came to a standstill. Tourism suffered. Even educational institutions stopped functioning. It is the loyal populace that suffered economically and emotionally. The recent emphasis on sustainability is a tacit admission of its leaders’ failures.

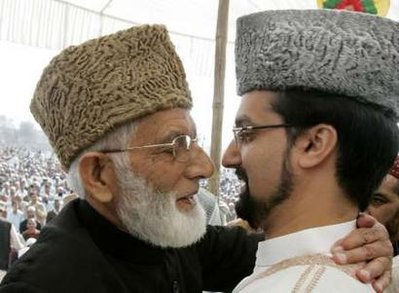

A Joint Resistance Leadership came into being, which included leaders Mirwaiz Umar Farooq, Syed Ali Shah Geelani and Yasin Malik. They issued weekly ‘calendars’ of protests. At long last, criticisms were voiced.

The three leaders issued a joint statement on Dec 14, 2016: “We have moved closer to our goal,” it claimed, and added, “Now it is time to consolidate our gains and build upon them in order to move ahead further. In this regard, the leadership feels that a long-term sustainable strategy, based on proactive initiatives, programmes, and sustainable modes of protest with maximum public participation in their creation and implementation and minimum costs for the people, is the way forward.”

The litmus tests are: popular inputs, minimum cost to the people, and sustainability in the long run. They would reach out to lawyers, artists, writers, artisans, students, traders, transporters and teachers “to discuss the idea with them, and seek their suggestions”.

To be sustainable, the strategy must not disturb the even tempo of life. Kashmiris are in a crisis that will not end soon. To begin with, it will not and cannot end without a settlement between India and Pakistan that also receives the people’s support. As Nawaz Sharif told visiting Indian journalists when he first became prime minister, the Pakistanis, Indians and Kashmiris must take a step back. Barring Mirwaiz Umar Farooq, none of the Hurriyat leaders show any inclination towards a compromise. One would have expected Kashmiris to press for a settlement, which cannot happen without compromise. But the very concept of compromise is unacceptable to Geelani and his associates.

If this section of the separatists dreads the very thought of compromise, the Indian establishment abhors the prospect of peaceful protest. This is its Achilles heel – masses out on the streets peacefully demanding azadi. This should be a prime element in the strategy. It is fully covered by the fundamental right to assemble peacefully without arms (Article 19.1.b) that the Indian constitution guarantees. Demand for respecting this right should be pressed relentlessly.

There is need for another fundamental shift, one that is long overdue. It is the descent of the Hurriyat leaders from their perches to the people, and their interest and involvement in the people’s many pressing issues. During the freedom movement, even the tallest leaders took part in humble municipal activities. On March 10, 1904, Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah was elected to Bombay’s municipal corporation. Sir Pherozeshah Mehta was already its member. Jawaharlal Nehru participated actively in Allahabad’s municipal corporation, as did Vallabhbhai Patel in the Ahmedabad corporation. The Hurriyat leaders need not contest elections to local bodies themselves, but they can encourage supporters to do so as individuals.

As part of this exercise, the leaders can interest themselves in the economic plight of the citizens and the many problems that beset traders, businessmen, students, teachers and the rest. In short, the Hurriyat should immerse itself in the plight of the people beyond feeding them slogans and demanding sacrifices of them. If the Hurriyat is to move forward and become relevant, it must be with the people and of it. This will strengthen the movement as well as lift the morale of the people. Such a strategy is pre-eminently sustainable. –c. Dawn