State-led demolitions and contested mosques deepen communal divides, raising concerns over due process and religious freedom

NEW DELHI – The Muslim community in India has witnessed a disturbing rise in state-led demolitions and disputes over their religious sites during the past year. The trend is visible particularly in states governed by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). According to data compiled by the Centre for Study of Society and Secularism (CSSS) from five major newspapers, there were 19 incidents of demolitions targeting Muslim-owned properties and 12 contested Muslim worship sites, including mosques and dargahs in 2024. Critics argue these actions reflect a pattern of systemic marginalisation, eroding constitutional protections and fuelling communal discord.

The CSSS reported 19 demolition drives across 10 states, with Uttar Pradesh recording the highest at five, followed by Maharashtra with four. Other incidents occurred in Delhi, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Assam. These demolitions affected over 500 structures, including homes, shops, mosques, and madrasas, predominantly owned or run by Muslims.

While state authorities often justified these actions, citing “illegal construction” or “encroachment,” many believe the demolitions were acts of collective punishment. In Mumbai’s Mira Road, 17 Muslim-owned structures were razed on 23 January, just days after communal tensions flared during the inauguration of the Ram Temple in Ayodhya.

“The bulldozers came without any notice. My shop and my livelihood were destroyed in hours,” said Mohammad Aslam, a local shopkeeper. Residents say no warning was issued, violating Article 21 of the Constitution, which ensures the right to life and property through due process.

In Bareilly, Uttar Pradesh, homes of Muslim residents were demolished following a clash during a Muharram procession. “They called our homes illegal, but we’ve lived here for generations. This is punishment for being Muslim,” said Hasan Ali, whose house was razed. In Udaipur and Assam, notices were served either on the day of demolition or afterward, raising concerns over the legality and fairness of the process.

The CSSS report identified procedural violations in several cases. In four incidents, including the demolition of Delhi’s historic Akhoondji Masjid, no notice was served. Of the 19 cases, only 11 had prior notices, most of which failed to meet the 30-day requirement under the law.

“This isn’t governance—it’s vendetta. The state is weaponising bulldozers against Muslims,” said Irfan Engineer, director of CSSS.

India’s judiciary has begun challenging these practices. On 2 September 2024, the Supreme Court, hearing a petition by Jamiat Ulama-i-Hind, ruled that demolishing homes as retribution for alleged crimes is unconstitutional. “Offences by an individual cannot justify bulldozing their family’s shelter,” the bench stated, hinting at the introduction of nationwide guidelines to prevent misuse.

On 6 November, the court ordered the Uttar Pradesh government to pay Rs 25 lakh in compensation for a 2019 demolition in Maharajganj, calling the state’s action “high-handed.” Justices BR Gavai and KV Viswanathan further criticised such demolitions on 13 November, describing them as “a lawless display of might is right.”

Despite these judicial interventions, demolitions persist. BJP leaders have often glorified bulldozers in political rallies, presenting them as symbols of strength against “lawbreakers”—a term critics believe implicitly targets Muslims.

“The messaging is clear: Muslims are portrayed as the enemy. This narrative fuels hate and justifies violence,” said Asaduddin Owaisi, president of the All India Majlis Ittehadul Muslimeen.

In parallel with demolitions, disputes over Muslim places of worship have surged. In 2024, right-wing groups laid claim to 12 mosques and dargahs, asserting they were built over former Hindu temples. Seven such cases were reported in Uttar Pradesh, with others in Maharashtra, Delhi, and Rajasthan.

In some cases, courts ordered surveys by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), while others permitted Hindu worship at contested sites, altering their character. In Sambhal, Uttar Pradesh, the 16th-century Shahi Jama Masjid became the focus of controversy after a survey on 19 November led to protests. Police fired on demonstrators, resulting in five deaths.

“We’ve prayed here for centuries. Now they call it a temple and kill us for protesting,” said Bilal Ahmed, a member of the mosque’s managing committee.

In Rajasthan’s Ajmer, a September lawsuit claimed that the dargah of Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti, a revered Sufi saint, was built over a Shiva temple. “This is our heritage, our faith. These claims are tearing communities apart,” said Syed Zainuddin, a trustee. The case is pending, but tensions are already running high.

These disputes challenge the Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act, 1991, which aims to maintain the religious status of sites as they stood on 15 August 1947. However, petitions questioning the Act’s validity have gained traction, emboldening right-wing outfits and raising fears of widespread unrest.

“The Act was designed to preserve communal harmony. Undermining it risks reopening historical wounds,” said historian Romila Thapar.

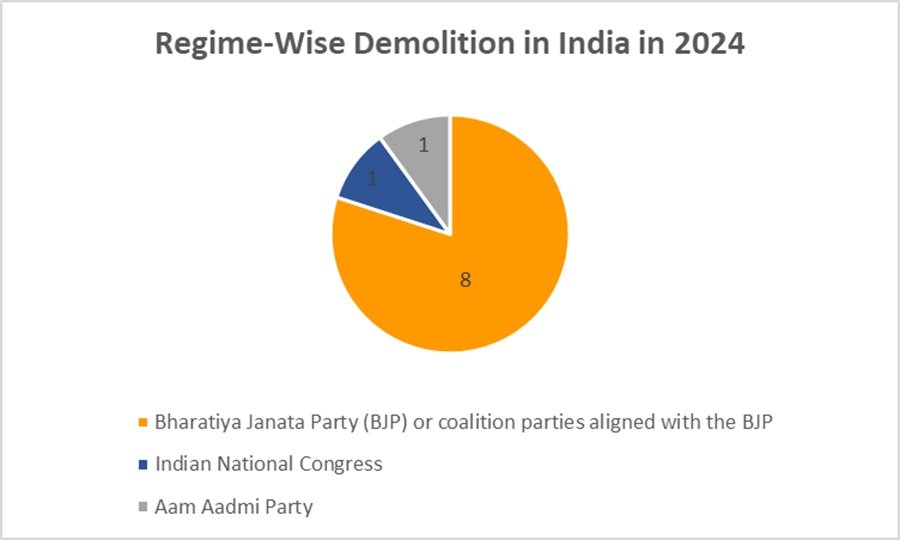

Activists and legal experts interpret the demolitions and religious site conflicts as forms of structural violence—a concept defined by Johan Galtung as systematic harm inflicted on marginalised groups through policies and institutions. In states ruled by the BJP, where 80% of the recorded demolitions occurred, observers see a worrying pattern.

“The state is using the law selectively, inflicting severe losses on Muslims—homes, businesses, and sacred spaces—without ensuring due process,” said senior advocate Dushyant Dave.

In Ghatkopar, Mumbai, Masjid Tahira and the Gulshan Ahmed Raza Madrasa were demolished despite having been regularised by the Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority (MMRDA). “We followed all legal procedures, yet our mosque was torn down. Where do we go for justice?” asked Mansoor Sheikh, a trustee.

In Mehrauli, Delhi, the centuries-old Akhoondji Masjid was demolished without any notice. The economic and emotional toll has been devastating. In Haldwani, Uttarakhand, over 250 Muslim-owned properties were destroyed, including a mosque and a madrassa, displacing hundreds of families.

“My children sleep on the footpath. We’ve lost everything—home, school, dignity,” said Rubina Khatoon, a displaced mother of three.

The rise in demolitions has coincided with inflammatory rhetoric from Hindu nationalist leaders and groups. Hate speeches frequently precede demolition drives, painting Muslims as encroachers or criminals.

In Chhatarpur, Madhya Pradesh, Shahzad Ali’s house was razed following protests against anti-Muslim remarks made by a Hindu cleric. “I was punished for speaking out in defence of my religion,” he said.

Organisations such as the Swaraj Vahini Association have filed petitions alleging that prominent mosques—including Jaunpur’s Atala Masjid—were built on Hindu temple ruins. These claims often lack credible historical evidence but still influence public discourse and judicial proceedings.

“This is about erasing Muslim identity and rewriting history to suit a majoritarian narrative,” said Zafarul Islam Khan, former chairman of the Delhi Minorities Commission.

While recent Supreme Court interventions have raised hope, rights groups insist that more robust action is needed to protect minority rights.

“Guidelines alone won’t stop this. Governments must be held accountable for violating constitutional norms,” said Shabnam Hashmi, a human rights campaigner. Legal experts are urging the Supreme Court to ensure that the right to notice, appeal, and fair hearing is not bypassed by state agencies.

For India’s 200 million Muslims, 2024 has been a year marked by fear, displacement, and despair.

“We’re not just losing homes or mosques—we’re losing our place in this country,” said Ayesha Begum, whose shop in Delhi was bulldozed in March. “How long must we keep proving we belong here?”

As India wrestles with its identity as a secular democracy, these incidents raise a pressing question: Will the state uphold the rule of law and equal rights, or will structural violence continue to erode the nation’s pluralistic foundations?