The Pressure to Escalate and the Monsters the US Wars Have Created in the Middle East

The Islamic State seems to grasp the nature of the mental landscape in the US far more clearly than we do. Whatever pain we cause it (and our bombing campaign is undoubtedly causing it some pain), we’re its ticket to the big time. Our war against it confirms its singular sense of importance in the world of jihadism. We have helped not just to bring it into existence (thanks to the invasion of Iraq and subsequent events there), but also to give it just the credentials it needs to thrive. Washington and the Islamic State are now attached at the hip and so the pressures for escalation will only grow

[dropcap]S[/dropcap]ometimes it seemed that only two issues mattered in the midterm election campaigns just ended. No, I’m not talking about Obamacare, or the inequality gap, or the country’s sagging infrastructure, or education, or energy policy. I mean two issues that truly threaten the wellbeing of citizens from Kansas, Colorado, and Iowa to New Hampshire and North Carolina. In those states and others, both were debated heatedly by candidates for the Senate and House, sometimes almost to the exclusion of anything else.

You know what I’m talking about — two issues on the lips of politicians nationwide, at the top of the news 24/7, and constantly trending on social media: ISIS and Ebola. Think of them as the two horsemen of the present American apocalypse.

And think of this otherwise drab midterm campaign as the escalation election. Republican candidates will arrive in Washington having beaten the war and disease drums particularly energetically, and they’re not likely to stop.

In 2015, you’re going to hear far more about protecting Americans from everything that endangers them least, and especially about the need for a pusillanimous president (or so he was labeled by a range of Republicans this campaign season) to buckle down, up the ante, and crush the Islamic State, that extreme Islamist mini-oil regime in the middle of an increasingly fragmented, chaotic Middle East.

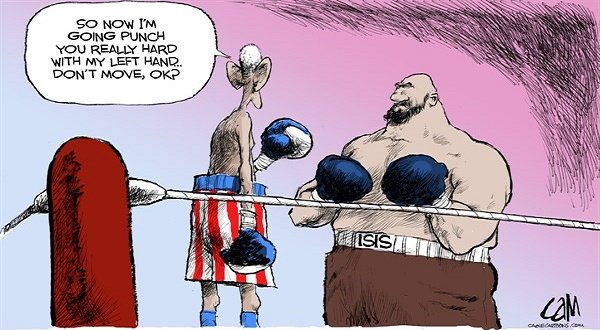

You already know the tune: more planes, more drones, more bombs, more special ops forces, more advisers, and more boots on the ground. After 13 years of testing, the recipe is tried and true, and its predictably disastrous results will only ensure far more hysteria in our future. And count on this: oppositional pressure to escalate, heading into the presidential campaign season, will be a significant factor in Washington “debates” in the last years of the Obama administration.

The Coming of a Terror Disease

Speaking of escalation, don’t think Congress will be the only place where escalation fever is likely to mount. Consider the pressures that will come directly from the Islamic State and Ebola. Let’s start with Ebola. Admittedly, as a disease it has no will, no mind. It can’t, in any normal sense, beat the drum for itself and its dangers. Nonetheless, though no one knows for sure, it may be on an escalatory path in at least two of the three desperately poor West African countries where it has embedded itself. If predictions prove correct and the international response to the pandemic there is too limited to halt the disease, if tens of thousands of new cases occur in the coming months, then Ebola will undoubtedly be headingelsewhere in Africa, and as we’ve already seen, some cases will continue to make it to this country, too.

Not only that, but sooner or later someone with Ebola might not be caught in time and the disease could spread to Americans here. The likelihood of a genuine pandemic in this country seems vanishingly small. But Ebola will clearly be in the news in the months to come, and in the post-9/11 American world, this means further full-scale panic and hysteria, more draconian decisions by random governors grandstanding for the media and their electoral futures. It means feeling like a targeted population for a long time to come.

In this way, Ebola should remain a force for escalation in this country. In its effects here so far, it might as well be an African version of the Islamic State. From Washington’s heavily militarized response to the pandemic in Liberia to the quarantining of an American nurse as if she were a terror suspect, it’s already clear that, as Karen Greenberg has predicted, the American response is falling into a “war-on-terror” template.

Keep this in mind as well: we’re talking about a country that has lived in a phantasmagoric landscape of danger for years now. It has built the most extensive system of national security and global surveillance ever created to protect Americans from a single danger — terrorism — that, despite 9/11, is near the bottom of the list of actual dangers in American life. As a country, we are now so invested in terrorism protection that every little blip on the terror screen causes further panic (and so sends yet more money into the coffers of the national security state and the military-industrial-homeland-security-intelligence complex).

Now, a terror disease has been added into the mix, one that — like a number of terror organizations in the Greater Middle East and Africa — is a grave danger in its “homeland,” just not in ours.

IS’s Escalatory Bag of Tricks

The preeminent terror outfit of the moment, the Islamic State (IS), which has declared itself a “caliphate” in parts of Iraq and Syria, seems to grasp the nature of the mental landscape in the US far more clearly than we do. Whatever pain we cause it (and our bombing campaign is undoubtedly causing it some pain), we’re its ticket to the big time. Our war against it confirms its singular sense of importance in the world of jihadism. We have helped not just to bring it into existence (thanks to the invasion of Iraq and subsequent events there), but also to give it just the credentials it needs to thrive. Washington and the Islamic State are now attached at the hip and so the pressures for escalation will only grow. Or put more accurately, they will be quite consciously stoked by the IS itself.

Bloody and barbaric as it may be, it’s also a remarkably resourceful movement with a powerful sense of how to utilize its propaganda skills, especially on the Internet, to attract recruits, gain support in worlds that matter to it, and drive the U.S. national security state and Washington over the edge. It can act or react in ways that will only lead the Obama administration to up the ante in its war.

As it has already done, it can continue to produce beheading videos and other inflammatory online creations, which have had a powerful escalatory effect here. It has also learned that it may, after a fashion, be able to call out the “lone wolves,” the loose nuts and bolts of our world, to act in its name. In recent weeks, there have been three such possible acts, one inNew York City and two in Canada by stray individuals who might have been responding, at least in part, to IS calls for action (though we can’t, of course, be certain why such disturbed people commit acts of mayhem). Such acts, in turn, trigger the usual sort of over-reporting and hysteria here as well as further steps to lock down our world.

What we do know is that the damage such individuals can do is modest at best, no more, say, than what a high school freshman with a pistol can do in a crowded cafeteria. Strangely, however, while mass shootings, which are on the rise in this country, get major headlines, they lead to few changes in our world. When it comes to the far less common phenomenon of the “lone wolf terrorist,” however, congressional figures are already raising a hue and cry and the national security state is mobilizing.

And then, of course, there’s what the militants of the Islamic State can do in Syria and Iraq to put further escalatory pressure on Washington. Despite the Obama administration’s bombing campaign, from the town of Kobane on the Turkish border to the outskirts of Baghdad the Islamic State has generally either held its ground or continued to expand incrementally in the last two months. Its militants are now within range of Baghdad International Airport, a key supply and transit point for the U.S., and recently dropped several mortar shells into the fortified Green Zone in the heart of the capital, which houses the gargantuan U.S. Embassy.

Already incidents of car bombings and suicide bombers are on the rise in Shiite neighborhoods of Baghdad. Imagine, though, what the next possible steps might be: an assault on the airport, Washington’s lifeline in the country, or the infiltration of even small numbers of fighters into neighborhoods in the capital and the beginning of actual fighting in the city. There are, in other words, a series of easily imaginable moves like these that could quickly raise temperatures and fear levels in Washington and lead to the kinds of escalatory steps that officially remain off the table at the moment.

Similarly, to imagine another kind of scenario, a State Department official recently suggestedthat U.S. air power be ordered to take out the pipelines that transport Islamic State-controlled oil to market. That was, she suggested, a “viable option” and was under consideration by the U.S. military. As energy expert Michael Klare has pointed out, however, attacking such pipelines “would provide anti-American groups anywhere in the world with a rationale for bombing pipelines on which we and our allies depend. The result could be global economic havoc.” In such a situation, the Islamic State could potentially call on “lone wolves” and jihadi groups across the Greater Middle East to respond in kind.

And these are simply examples of moves the Islamic state could have in its own escalatory bag of tricks.

The Military Trumps the Commander-in-Chief

At least one more source of potential pressure must be added to Congress, Ebola, and the Islamic State: the Pentagon. Thanks to the reporting of Mark Perry at Politico, we know that the most telling bit of domestic escalatory pressure on the president came directly from someone he reputedly respects greatly, General Martin Dempsey, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. On August 6th, Perry writes, Dempsey joined Obama in his limousine and, according to an unnamed “senior Pentagon official,” “really leaned into him” on the crisis in the Middle East, saying that it demanded “immediate attention.” A series of White House meetings followed and the next evening the president went on national television toannounce the first limited air strikes against the militants of the Islamic State. By early the following month, he had essentially declared war against that outfit and announced “a systematic campaign of airstrikes,” as well as other measures.

Another manifestation of military pressure on the White House soon followed, however. From the beginning, the president had repeatedly and insistently taken one thing off that famed “table” in Washington on which all “options” reputedly sit: the possibility that there would ever be American “boots on the ground” in Iraq — that is, military personnel sent directly into combat. This, in effect, represented what was left of Obama’s previous proud claim that he had gotten us out of Iraq never to return. Assumedly, it also represented a bedrock formulation in a situation that otherwise seemed to be in a constant state of flux.

In a way that has been rare in the history of American civilian-military relations, Dempsey and others in the Pentagon simply refused to accept this. No matter what the commander-in-chief’s bottom line may have been, they evidently saw the future quite differently and didn’t hesitate to say so. On September 16th, Dempsey himself stepped gingerly across the red line the president had drawn in the shifting sands of Iraq and Syria, telling the Senate Armed Services Committee in public testimony, “If we reach the point where I believe our advisers should accompany Iraqi troops on attacks against specific [Islamic State] targets, I will recommend that to the president.”

In response, the president addressed troops at MacDill Air Force Base in Florida the next day and reiterated his stance: “I want to be clear: the American forces that have been deployed to Iraq do not and will not have a combat mission.” Meanwhile, officials at the White House and in the Pentagon “scrambled” to claim that the difference was merely a semantic one and in no way an attempt by the chairman of the Joint Chiefs to contradict presidential policy.

That was, however, clearly not the case. Soon after, Secretary of Defense Hagel offered a similar, if blurry, mantra on the subject of boots on the ground: “Anybody in a war zone, who’s ever been in a war zone, and some of you have, know that if you’re in a war zone, you’re in combat.” Almost a month later, Dempsey himself returned to the subject. Speaking about a future campaign by the Iraqi army against that country’s second largest city, Mosul, in the hands of the Islamic State since that army collapsed, he elliptically indicated his belief that American advisers would sooner or later be heading into battle with Iraqi troops. “Mosul will likely be the decisive battle in the ground campaign at some point in the future,” Dempsey told ABC’s “This Week.” “My instinct at this point is that will require a different kind of advising and assisting because of the complexity of that fight.” More recently, he urged that American advisors be sent to the battle zone of Anbar Province.

Meanwhile, retired officials like former Secretary of Defense Robert Gates (“There will be boots on the ground if there’s to be any hope of success in the strategy. And I think that by continuing to repeat that [the U.S. won’t put boots on the ground], the president, in effect, traps himself.”), as well as the usual anonymous sources, drove the point home. If the not-so-subtle public defiance of presidential policy was striking, the urge itself was perhaps less so.

After all, a group of frustrated military men would have had no trouble grasping the obvious: that U.S. air power, a coalition of unenthusiastic regional allies (some of whom had aided IS and other extreme al-Qaeda-style groups in their rise), Syrian “moderate” fighters who essentially couldn’t be found, and a sectarian Iraqi government with an army that wouldn’t fight did not add up to the perfect formula for winning a war in the Middle East. With their feet already on the lower rungs of the escalatory ladder, their response was to begin promoting the need for more American involvement, the commander-in-chief be damned.

And note that the impulse to contradict the president in an escalatory fashion wasn’t confined to the fight against the Islamic State. When it came to Ebola, Dempsey, Hagel, and Army Chief of Staff General Ray Odierno set out on a similar path in an even blunter fashion.

As October was ending, the president firmly called on state governors and others not to impose blanket quarantines on American caregivers returning from West Africa, but to stick to the guidelines suggested by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Almost immediately thereafter, Odierno issued a directive for the “21-day controlled monitoring” of all troops returning from the region (even though those there were not supposed to treat Ebola patients themselves). Soon after, Dempsey recommended to the secretary of defense that “all members of the armed services working in Ebola-stricken West African countries undergo mandatory 21-day quarantines upon their return to the United States.” Hagel no less promptly ordered just such a quarantine for troops returning from the Ebola hot zone.

The president was left to explain lamely and less than coherently the divergence between his policy and the Pentagon’s. As the New York Times reported, “In his remarks, Mr. Obama defended the CDC guidelines for civilians, saying they protect Americans at home while not unduly burdening health workers in Africa. He called the situation with members of the military different, in part because they are not going to Africa voluntarily. ‘We don’t expect them to have similar rules, and by definition, they’re working under more circumscribed circumstances.’”

A President Adrift in Bad Weather

In the eye of this storm of pressures is, of course, the White House and a president who seems aware that, in the last 13 years, American military power in the Greater Middle East has not exactly achieved its goals. And yet, that clearly matters little.

We’ve been through a version of this before in the Vietnam era. We know that, once on the ladder of escalation, those in power, including presidents, often can’t imagine any possible direction but up, no matter how they assess where that might lead. A mentality of fatefulness verging on helplessness seems to set in, which only results in an ever-greater commitment of American resources (and lives).

Under the pressure of a powerful national security state (and the various complexes that have grown to gigantic proportions around it), in a Washington in which beating the drums for war has become a reflexive act and Republican hawks may well rule the roost, in a society in which journalistically stripped-down major media outlets are focused on anything that can glue eyeballs for more than a few seconds (and the Internet and social media follow suit), it turns out to be remarkably easy to create an atmosphere of hysteria, and escalation naturally follows. Never before have Americans experienced the intensity of this combination of forces in this way.

As for the Obama White House, increasingly imperial in theory, it has visibly stumbled in practice. Worse yet for a president clearly adrift, what it has to work with in the world looks ever less promising. Take, as an example, its ally in the war against the Islamic State, the Iraqi government of Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi. He has been touted as a Shiite “unifier” unlike his notoriously sectarian predecessor Nouri al-Maliki.

Facts on the ground, however, tell quite a different story. It turns out that, in the wake of the collapse of the Iraqi army in the northern part of the country, the only significant forces capable of defending the capital and Shiite regions to the south have proven to be highly sectarian Shiite militias.

According to recent reports, in places where they have taken territory, they have acted in a fashion hardly less brutal than their IS enemies. They have burned homes in villages they have captured, kidnapping and killing Sunnis in a grim repeat of the worst years of sectarian slaughter during the American occupation. In the meantime, al-Abadi appointed as his crucial interior minister Mohammed Ghabban, a man connected to the Badr Organization, whose Shiite militia was once known for its death squads.

Everyone seems to agree that the prerequisite for any struggle to defeat the Islamic State is a genuine “unity” government that could begin to woo back the alienated, oppressed Sunni population of northern Iraq. That, however, is simply not in the cards. In response to this fact on the ground, Washington has only one conceivable option: further escalation. It’s the nature of the world that presses in on the White House, even if the phrase the ladder to hell makes no metaphorical sense.

Escalation is now a structural fact embedded in the war in the Middle East and the Ebola crisis here at home. It has its constituencies and they are powerful. It is fed by a blend of hysteria and panic that now passes for “the news,” heightened by the ministrations of the social media. Escalation, it turns out, is in the interest of everyone who matters — except us.

Copyright 2014 Tom Engelhardt www.tomdispatch.com