Born a bird trapper, Ali Hussain from Bihar became a guardian of India’s birds, working alongside top scientists and proving how traditional Muslim knowledge can serve the world’s wildlife

NEW DELHI/PATNA – When people first saw Ali Hussain walking through the fields of Bihar with bamboo cages and handmade nets, many thought he was just another bird catcher, and many called him that for years. But few understood what really made him special.

Ali Hussain, a quiet man from a family of traditional bird trappers, was more than what the eye could see. Behind his soft smile and weather-worn hands was a lifetime of wisdom passed down over generations. He had learnt to follow bird calls, understand their movements, and craft traps not to harm them, but to study and help them survive.

In the early 1960s, Hussain’s life changed forever. He met Dr Salim Ali, India’s most famous ornithologist, often called the “Birdman of India.” It was the start of a deep friendship and a shared mission. Instead of catching birds for trade, Hussain began working with scientists to catch birds for research and conservation.

“I had never met anyone like him,” Dr Salim Ali had once told colleagues at the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS). “He handled birds like a doctor treats a child. Gently, with care. He knew more about them than many of us.”

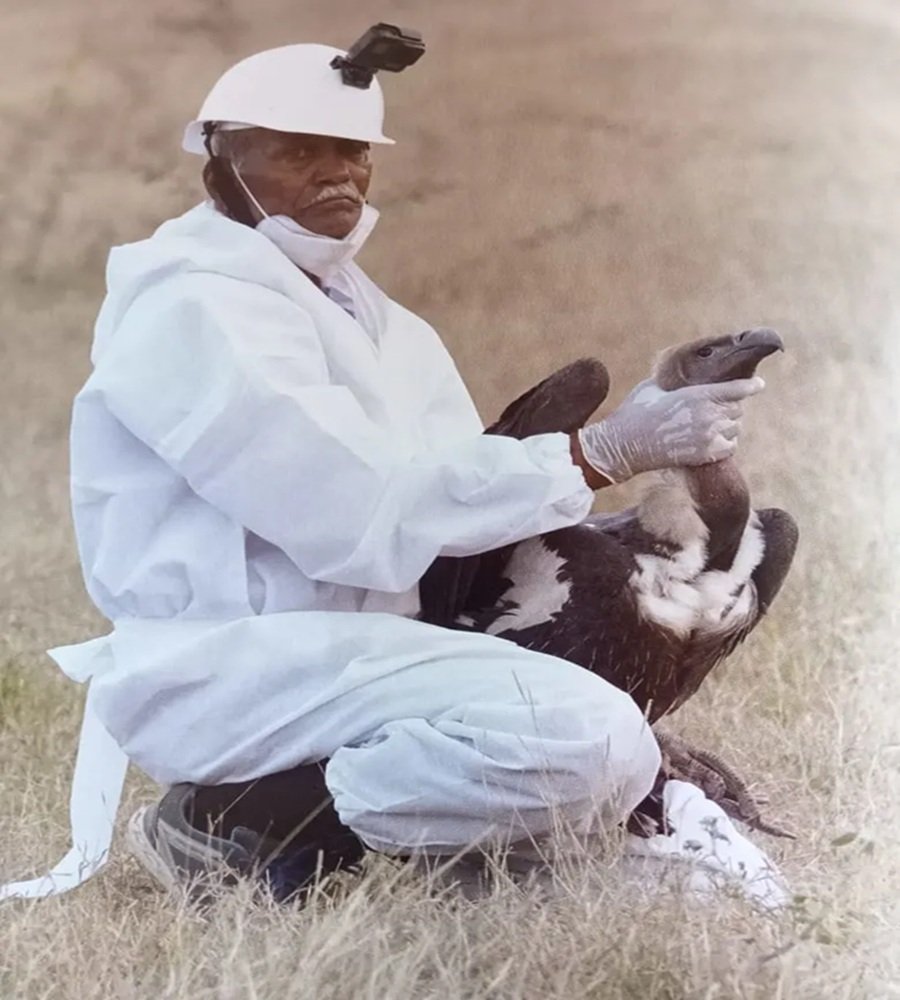

Ali Hussain helps capture and tag a vulture in Gir National Park. – Photo: Wildlife Division, Sasan-Gir, Gujarat

Hussain began travelling with BNHS teams across India, using his age-old skills to help ring thousands of birds. These rings, placed on birds’ legs, allowed scientists to track their migration and breeding patterns. And each bird was returned safely to the sky.

His fame didn’t stop in India. In the 1990s, American scientists from the Whooping Crane Recovery Programme invited him to the US. The whooping crane is one of the rarest birds in the world. Catching them was almost impossible until Hussain arrived there.

In just a few weeks, he safely captured 10% of the entire population without harming a single bird.

One American official said, “We were shocked. He caught birds we couldn’t even get close to. And they were all unharmed. It was a masterclass.”

For years, conservation efforts across the world relied mostly on modern technology — drones, satellites, and lab studies. But Ali Hussain showed that indigenous knowledge also has value.

“He never went to school,” said Mohammed Salim, one of his sons. “But he could read nature like a book. He knew where birds would land just by feeling the wind.”

His Muslim identity and simple lifestyle never stopped him from working with international scientists. In fact, it reminded many that people from rural and minority communities have a lot to offer when they are trusted and respected.

Even in his 80s, Ali Hussain never stopped helping. Young researchers from across India still come to his home in Patna, Bihar, asking him how to catch birds safely. His sons, trained under him, now assist with bird studies and continue the family’s work.

“Abba used to say, ‘Don’t hurt what sings. We’re here to protect, not harm,” recalled his eldest son, Iqbal Hussain.

For them, bird trapping was never about money. It was about respect — for life, for tradition, and for the Creator’s creation.

Despite his international praise, Ali Hussain was rarely honoured by Indian government bodies. No national award. No Padma Shri. No headlines on TV. Many believe this is because he was poor, Muslim, and from Bihar.

“People like him don’t fit the official image of a ‘scientist’,” said Prof Neelima Ghosh, an ornithologist from Delhi University. “But make no mistake, he taught us what our books couldn’t.”

Foreign universities invited him. Wildlife departments in the US and UK mentioned him in reports. Yet in India, he was mostly seen as “just a bird catcher.”

Ali Hussain’s connection with birds wasn’t just scientific — it was spiritual.

In many interviews, he said he felt that protecting birds was part of his faith as a Muslim. Islam teaches kindness to all living creatures, and he took that to heart.

“Birds pray too,” he once told a young researcher. “If we harm them, we stop their prayer.”

Ali Hussain sets traps to capture the Bengal florican in Pillibhit Tiger Reserve. Photo: Asad Rahmani taken from roundglas sustain

Today, his sons — Iqbal, Rashid, and Shafiq — run workshops on bird ringing and safe trapping. They continue to work with scientists from India and abroad.

“We grew up watching him work,” said Rashid. “He never rushed. He would wait for hours just to catch one bird the right way. Now we are doing the same.”

They are also trying to collect and record his trapping methods, which risk being lost as modern technology takes over. Many young Muslims from Bihar and West Bengal now visit the Hussain family to learn these skills.

In a country where Muslims are often shown in a bad light or made to feel like outsiders, Ali Hussain’s story is a powerful reminder of their quiet contributions. He didn’t protest, shout, or demand attention. He just kept working, helping both birds and humans.

“Ali Hussain should be in our school books,” said Dr Ramesh Gupta, a conservation writer. “Not because he was a Muslim, but because he was a great Indian.”

But maybe he deserves to be remembered because he was a Muslim too — a man who used his traditional knowledge, passed from father to son, to help save the very species others hunted.

He was not a scientist in the traditional sense. He didn’t wear a lab coat or speak English. He didn’t write research papers or held press conferences.

But to every bird that flew free because of him, and every student who learnt the gentle art of trapping from him, he was a scientist of the highest order.

He belonged to a generation of Muslims whose knowledge came from the land, who learnt by watching, listening, and respecting life around them.

India may not have celebrated him fully in his lifetime. But the birds did. And that’s something to think about.