On the first anniversary of Afzal Guru’s hanging, it may be important for the Indian state to introspect what his execution achieved

ANURADHA BHASIN JAMWAL

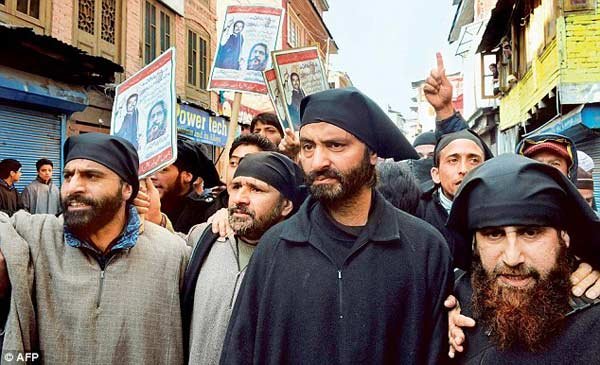

[dropcap]L[/dropcap]AST year this week (Feb 9), the Kashmiris added to their unique calendar of horrifying memories a date that, like February 11, wouldn’t need any reminders. As the valley observes the first anniversary of Afzal Guru hanging, perceived to be a major travesty of justice, it is a grim reminder of the end of the last vestiges of trust and confidence in Indian government, whatever little remained of it, weaning away even the fence sitters and the pro-Indian ordinary civilians, shocked by the brutality and arrogance of sending a Kashmiri man, not sufficiently proved guilty, to gallows for satiating the “collective conscience of the society” and for the vote-bank greed of the Congress.

The double ended jinx not only numbed the senses of people in Kashmir, it also left Congress in doldrums just before general elections. One man’s hanging even failed as an election strategy, the execution having sadly come just before the apex court ruling de-legtimising the long wait on mercy petitions.

Afzal Guru’s case would have easily qualified for commutation of his capital punishment to life term, had Congress acted with greater pragmatism and saved Kashmir from slipping into a whirlpool of dismay from which recovery is now almost impossible.

The spiral of anger over Afzal Guru’s hanging stemmed not only from what Kashmiris believed was unfair or for its symbolism of Indian arrogance in Kashmir, it was also pushed forth by years of accumulation of mistrust, sufferings and waves of repression and denial to either resolve the long pending Kashmir dispute or to address the vital question of human rights – more so, after 2008 and exacerbated by 2010 killings.

The hanging, carried out as per a verdict that denied Guru a fair chance of defense, and the way he was sent to gallows, in complete secrecy with no information to his family and no chance of that last meeting, coupled with the complete siege of the Valley just hours before his execution for over a week altogether, pushed Kashmiris further into a recession of isolation, humiliation and anger turning Kashmir into a dangerous simmering volcano, even as it may on the surface appear quite normal.

Treating it may be a monumental herculean task, requiring extra-ordinary conviction and sensitivity from central government, which has been in extremely short supply in recent years. The official closure on Pathribal case recently only demonstrates how far and in an opposite direction, the country may be from this remedy.

On the first anniversary of Afzal Guru’s hanging, it may be important for the Indian state to introspect what his execution achieved. Massively adding to the sense of injury of Kashmiris, it has further strengthened the resilience and resistance of the people, making its signs visible in a myriad ways, some of which are potently dangerous.

It has brought to fore a young generation of Kashmir, strongly articulate in their creative expression of their resistance, a generation that knows no fears and is unwilling to be bogged down by the dichotomies of complex layers of the Kashmir conflict but rather finding ways and means to grapple with it.

But it has also brought up a generation that finds itself so pushed to the wall that it tends to re-glamourize the role of the gun with a much greater ferocity that the region witnessed two decades back.

It may be crucial to grope for answers to the question why a population that rejected the gun about more than a decade ago would again find its lure attractive, signs of which are visible in the renewed respect that the militant now commands and in the way some of the youth have begun joining the ranks of militant organizations.

The Kashmiris may need to learn the trick of realizing the self-destructive nature of a violent struggle and understand the rich potential of the form of resistance that would eventually be more sustainable, even if slow. But the space for rationality further shrinks with the enlarging shadows of the state’s belligerent mood.

People perceive Afzal Guru in different ways – a man who didn’t get a fair trial, a pawn, a victim or a hero. Whichever way he is looked upon at, his execution is a memory that has had a scarring effect and will go down in history of Kashmir as one of the most ghastly memories ever. Both Maqbool Butt hanging in 1984 and Afzal Guru’s exactly 19 years later are important landmarks in Kashmir’s history, and instructive of the massive upheavals they brought.

The first aided the course of young men going across the borders and returning with the gun. The second has bestowed a lethal ferocity to that gun with a renewed vigour. Jammu and Kashmir, particularly, the Valley today, hides beneath its surface a volcano ready to explode from within.

The 2014 US pullout from Afghanistan and larger global picture of India-Pakistan relations in that context can only provide a little spark from outside but there is enough ammunition within even without that.