At a time when politicians have come down to the level of street urchins, hurling abuses at each other and when the surveillance of even an individual is not considered an intrusion to privacy, the memory of the late prime minister, Inder Kumar Gujral, is like a breath of fresh air. He was urbane, civil and never raised his voice when an opponent lost his cool. This November 30 is his first death anniversary.

Throughout his political career, either as foreign minister or as prime minister, he tried to bring back the values. As foreign minister, he advocated morality in dealing with big and small countries. He was opposed to taking action against Saddam Hussain. The West regretted the elimination of Saddam when it found that he had no weapons of destruction.

In his book, A Foreign Policy for India, Gujral says: “Indian foreign policy was not something which we read about in text books or heard about at the university. It was a product of the freedom struggle itself. Resisting oppression meant independence and was spelt out as the defining characteristic of an independent policy.”

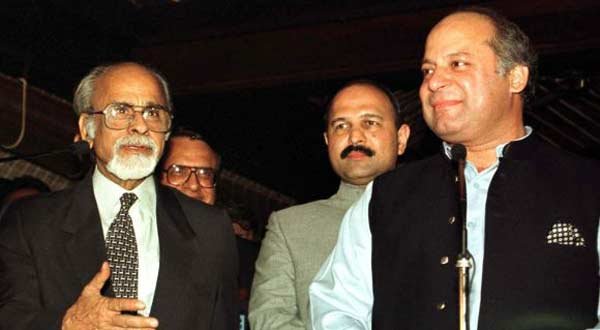

Gujral was particularly partial to India’s neighboring countries, something that came to be known as the Gujral Doctrine. I am certain that he would have accommodated Bangladesh on the Teesta River water, a concession which would have helped Bangladesh Prime Minister Shaikh Hasina to win the elections due in January next. Similarly, Gujral would have found a way to hold talks with Pakistan instead of sticking to Islamabad’s guarantee to ensure that the Line of Control (LoC) was sacrosanct. When Pakistan is itself in the midst of combat with terrorists, particularly the Taliban, it is difficult to guarantee no violation of the LoC because there are non-stake holders disturbing peace.

I came to know Gujral when he was a member of Indira Gandhi’s “kitchen cabinet” after she lost to Lal Bahadur Shastri in the race to the prime ministerial gaddi (seat). She demanded unstinted loyalty and Gujral was her confidante. Yet, when Indira imposed the emergency, he refused to toe the line as minister for information and broadcasting. Indira’s son, Sanjay Gandhi, an extra-constitutional authority, was running the government. Sanjay phoned up Gujral, asking him to propagate against Jayaprakash Narain, heading the movement to remove corruption and to resist the authoritarianism which Indira’s rule had come to represent. Gujral told Sanjay that he was Indira’s minister and not his errand boy. Gujral was transferred from the Information and Broadcasting Ministry to the Planning Commission, where P.N. Haksar, once Indira’s principal secretary, was hibernating. He too had been punished for having joined issue with Sanjay.

It was only the offer of ambassadorship to the Soviet Union which stopped Gujral from resigning from the government. Being a leftist – he was a camp follower of the Communist Party during his student days at Lahore – he did so well in Moscow that he was requested by Morarji Desai, the then prime minister, to continue as India’s envoy. Gujral had ingratiated himself with the Communist Party and the government so closely that the Soviet Union was unsparing in supplying arms to India. Moscow also stood by the side of New Delhi on Kashmir.

Gujral, though, had a weakness – his love for Pakistan, where he was born. He sincerely believed that a friendly Pakistan was an asset to India. He would have criticized the firing of Pakistan television channels for showing the Indian programs more than permitted. Both countries are guilty of harming each other’s credentials relating to the news and political enormity. Viewers are mature enough to separate propaganda from happenings.

His first love was for Punjab. When he was prime minister, he wrote off the state’s debt to the Centre running into tens of millions. He also sanctioned a Science City to be founded at Jalandhar, where he and his family had settled after migrating from Jhelum. And while out of office, he spanned the distance between the Hindus and Sikhs during the militancy years. He constituted the Punjab Group – I was its member – to talk to the Akalis on the one hand and the chauvinists on the other.

After the fall of Deve Gowda government, Gujral became the prime minister for a brief period. Earlier, he undertook a tour of South Africa and Egypt in October 1977. I accompanied him as a journalist. My purpose was to see the country where Mahatma Gandhi had experimented with his satyagraha (insistence on truth) – an antidote to the class struggle, because a satyagrahi was required to purify himself in order to serve the society without any ulterior motive. Gujral visited the Pietermaritzburg railway station, where a pamphlet was available relating how Gandhiji was thrown out of a first-class railway compartment exclusively reserved for the whites.

My long-cherished desire to meet Nelson Mandela came true as I joined Gujral during a banquet dinner hosted in his honor. Later that night, Mandela broke into dance and dragged Gujral on to the floor. Gujral’s bonanza to government servants on the recommendations of the pay commission was too heavy a burden on the exchequer at a time when India was not in sound economic health. Had he implemented the other recommendations, such as the 30 per cent cut in the bureaucracy and extended working hours, some balance might have been struck. But Gujral was under pressure from trade unions and the Left. The hike destabilized the Central budget and was beyond the capacity of the states when they too were obliged to follow suit.

It is strange how the dust of time accumulates to obscure even the names of people who have served the country well in its most difficult times. The Congress party he served, practically his whole life, is opposed to him because he tried to bring back the party to its ethos of democracy, pluralism and egalitarianism. It is, indeed, a pity that values have ceased to matter with political parties. Gujral would not have fitted in the Congress or any other party if he had been living.