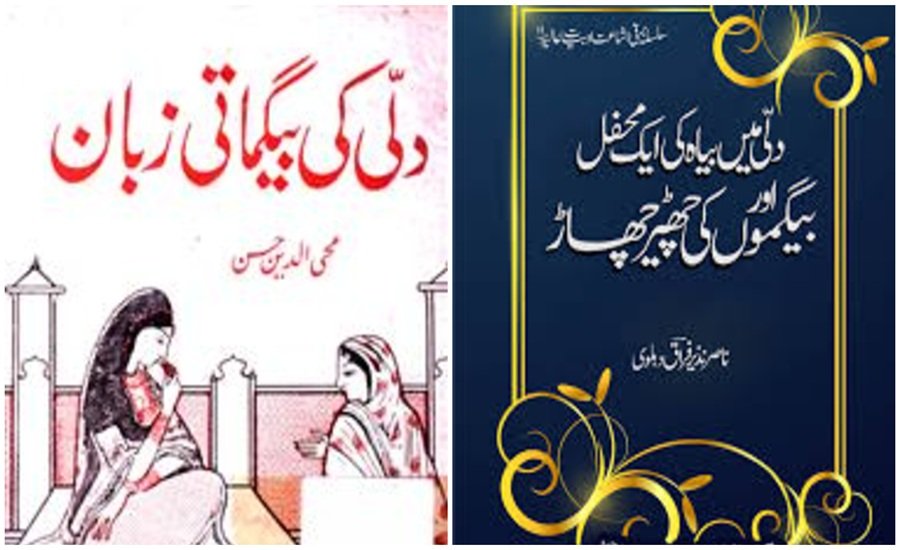

Once confined to royal palaces, the Begmati language shaped the unique feminine idioms of Muslim households but now survives only in whispers and memories.

NEW DELHI — In the narrow lanes of Old Delhi, the echoes of a unique language once spoken behind the veils of royal and noble Muslim households are gradually fading. Known as the Begmati language, this distinctive way of conversation carried the idioms, proverbs, and expressions exclusive to the women of the forts and palaces — a language that was as much about identity as it was about communication.

Sania, a doctoral researcher from Jamia Millia Islamia University studying the Begmati language, explains that “Begmati language is actually Urdu, but used in a very special way during conversations among women.” She notes that it was initially limited to the ladies of forts and royal palaces, who communicated through a code rich in kitchen-related idioms and feminine references.

“After the political turmoil in Delhi, this language spread beyond the confines of the forts and into the streets of Old Delhi,” Sania says. “Even today, many old families in Delhi retain the flavour of Begmati language in their speech.”

The Begmati language thrived as a cultural vessel among women — grandmothers, aunts, sisters, daughters, and household maids — who managed and nurtured the home. Sania remarks, “The language women spoke had a completely different flavour, a vocabulary distinct from that of men. Just as men’s conversations were incomplete without poetry, women’s speech was never without proverbs or idioms, sometimes sharp with scorn, other times filled with desire.”

One example she shares is the word ‘Nikhto’, once used to describe women who were considered impolite or outspoken — a word now absent from modern male speech. Another charming idiom contrasts male and female speech: men might say “Reinhold the tongue” to tell someone to be quiet, referencing horse riding, but women, unfamiliar with horses, would say, “Is the stitch of the tongue broken?” borrowing from the language of sewing and embroidery.

The deep roots of Begmati language lie in everyday female experiences — kitchen work, childcare, household management — shaping a linguistic heritage that remains unique. Sania adds, “Many proverbs related to maternal care or household chores are pure Begmati. For instance, if someone repeatedly visits a place, it’s said their ‘umbilical cord is stuck there,’ a phrase reflecting the language’s intimate connection with womanhood.”

Despite its rich cultural value, the Begmati language is now nearly extinct. Social reformers in the 19th century, including figures like Deputy Nazir and Hali, criticised it as a “bad language,” leading to its decline. The spread of education among girls also meant that standardised languages replaced the once-vibrant Begmati. “Begmati language is no longer in vogue,” Sania laments. “It was not preserved strictly because there was no need, and much of what remains has been recorded by male writers raised in women’s homes.”

The word ‘Begum’ itself hints at class and caste dimensions embedded in the language, which also found variants in places like Lucknow, Bhopal, and the Deccan region — areas with strong veiling traditions and feminine cultures. “The songs and speech of women in Hyderabad, for example, have a melody and rhyme much like the Begmati language’s rhythm,” Sania observes.

Political and social changes in the 19th century further pushed the language into obscurity. As wealth and status became more important, “people lacked taste,” and the Begmati language was dismissed as the talk of a “special kind of women” who should not be emulated. Sania quotes a popular saying mocking women of the time: “I forgot the lime, I forgot the tot, I started eating wheat, I started sleeping on khat,” illustrating how Begmati was ridiculed and sidelined.

Yet the language’s musicality and self-mockery shine through in its verses: “Wood burns like coal, coal burns like ash, I don’t burn coal like ash,” a phrase women would use to express frustration or resignation with their fate.

Today, while the Begmati language no longer flourishes as it once did, its traces linger in the conversations of old Delhi’s Muslim families — a living heritage of a time when women’s voices spoke their own truths behind palace walls.